Christian Russau (Forschungs- und Dokumentationszentrum Chile/Lateinamerika e.V. - FDCL):

Enforcement of international trade regimes between the European Union (EU) and the Common Market of the South (MERCOSUR)? Foreign Direct Investment as the object of free trade negotiations: Between investors' rights, development and human rights

Translated by Jan Stehle, ed. FDCL-Verlag, Berlin, January 2004

Download [pdf 2.519 KB]

1. The European Union (EU) and the Common Market of the South (MERCOSUR)

1.1 Negotiations of the "Interregional Association Agreement"between the EU and MERCOSUR

After having signed a treaty of inter-institutional cooperation in May of 1992, MERCOSUR and the EU sealed an Interregional Framework Cooperation Agreement on the opening of negotiations for a free trade agreement between both regions in 1995. The negotiation modalities had been agreed upon at the Summit of the Heads of State from the EU, Latin America and the Caribbean in June of 1999 in Rio de Janeiro. As a result, since the end of 1999 the EU and MERCOSUR have been meeting at semi-annual sessions of the Bi-regional Negotiations Committee (BNC) to negotiate the establishment of an interregional association agreement.

"[A] political dialogue, a co-operation pillar and a trade chapter [...,] the main objective of the 1995 Framework Agreement is the preparation of negotiations on an Interregional Association Agreement between the EU and MERCOSUR, which should include a liberalization of all trade in goods and services, aiming at free trade, in conformity with WTO rules".[1]

Starting in 2005 a joint free trade area is planned to be gradually introduced.

Parallel to these negotiations between the EU and MERCOSUR the American countries are negotiating the establishment of a Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA/ALCA/ZLEA). At the Summit of the Americas in Miami in 1994, 34 American heads of state (with the exception of Cuba) had accorded to create the Free Trade Area of the Americas.

Negotiations there should formally follow the principles of "consensus", "transparency", "consistency with WTO-rules" and "single undertaking", to ensure that bilateral and sub-regional agreements remain unimpaired and so that "special attention will be given to the needs of the smaller economies".[2] Negotiations should conclude by 2005 and the Free Trade Area of the Americas with 780 million potential consumers should be in force by the end of 2005. At the VIIIth Conference of Ministers of the FTAA negotiation process in Miami from November 20-21, 2003, the principle of single undertaking was addressed, so that at first only those areas would be discussed, to which every potential membership candidate was willing to grant unrestricted market access. This, according to the majority of the international press, would constitute a pioneer innovation and consequently the concept could be described in terms of a FTAA light, or even a FTAA à la carte. But this view is to some extent short-sighted, since the most controversial issues, like investment and public procurement policy, have not been erased from the agenda of negotiations, but have been merely temporarily postponed.[3]

At the same time negotiations within the World Trade Organization (WTO) on the worldwide liberalization of markets is under way. The Fourth Round of Ministers, the highest decision-making body of the WTO, at their meeting in Doha, Qatar in November of 2001, had decided on the topics of the new world trade round (Qatar Round). The main topics of the Doha-Agenda, which officially functions under the title "Doha-Development-Round", are the liberalization of trade of goods and services and investment, as well as intellectual property rights.[4]

The proposed objectives of these multilateral negotiations are free market access, while taking into account the WTO principles of the National Treatment (NT) and the Most Favored Nation Clause (MFN). These "non-discrimination" rules of the WTO define National Treatment as equal market access opportunities for national as well as international suppliers, which cannot be restricted by local, regional or national law. Most Favored Nation Clause means that all trade-related advantages, which are granted to a WTO-member country have to be granted to all other members as well. According to the original schedule the Doha-Agenda should be passed in 2005. But after the "failure" in Cancún and due to the existing divergences, which could not be resolved at the WTO December meeting in Geneva, the original timetable has gone a bit off course, or is, so to say, temporarily broken off. Given these circumstances, the focus of attention has once again been placed on bilateral negotiation levels, which of course include the negotiation process between the EU and MERCOSUR.

After negotiations began between MERCOSUR and the EU at the end of 1999, new points were set within the framework of "political dialogue" and "cooperation" at the IInd Summit of Heads of State of Latin America, the Caribbean and Europe in Madrid in May 2002. The final political discussions on the free trade agreement are anticipated to take place by the heads of state at the IIIrd Summit in Guadalajara/Mexico from May 28-29, 2004. Based on the renewed offers to negotiate the mutual "liberalization" of markets and market access, which are planned for April 15, 2004, the agreement could be signed by October 2004.

A similar agreement of the so-called "fourth generation" was signed by the EU and Mexico in 1997 and came into force in October 2000 (it is also referred to as the "Global Agreement"). The association agreement between the EU and Chile was signed in November 2002 and came into force in February 2003.

1.2 Trade - Development?

Negotiations on the "liberalization" of market access and trade of goods and services seem to take place everywhere these days.

EU Trade Commissioner, Pascal Lamy, judges the comprehensive opening of market access within the framework of WTO negotiations as follows:

"WTO-members must further liberalize access to markets for goods and services, on the basis of predictable and non-discriminatory rules. Agriculture, services and non-agriculture tariffs are all key-areas for improving market access."[5]

Lamy views development as a consequence of this "liberalization" of trade:

"Trade and investment liberalization offer great opportunities for economic growth and sustainable development."[6]

With regards to the Free Trade Area of the Americas that is to be created, the U.S. Trade Representative, Robert B. Zoellick, has a similar view:

"A Tariff-Free World: Every corner store in America becomes a duty-free shop for working families."[7]

The WTO ministerial declaration of Doha [WT/MIN(01)/DEC/1, 20 November 2001] defines the relationship between trade and development in a similar way:

"International trade can play a major role in the promotion of economic development and the alleviation of poverty."[8]

The negotiations about opening up markets like the multilateral negotiations of the WTO, the regional ones within the framework of FTAA as well as the bilateral ones such as the MERCOSUR-EU negotiations, are driven by the strong belief that free trade and development are closely linked. It can be gathered from interregional press sources, that the agricultural sector is the key issue in all international negotiations. One of the main reasons for this is that all parties involved regard the question of agricultural subsidies for exported goods and internal production as one of the most sensitive issues . Additionally, limited market access for agricultural products from the "South", due to tariffs or phytosanitary trade barriers of the "North", constitute in the eyes of many countries, who belong to the Cairns-Group, non-tariff trade barriers that only serve to advance the protectionism of the "North".[9] According to estimates, subsidies of OECD countries that were used to protect their own agricultural markets averaged 360 billion US-dollars annually.[10]

Thus, it is not surprising that in the negotiations between the EU and MERCOSUR the agricultural sector is considered to be the central issue of negotiations. In addition, the trade of agricultural goods is the only trade sector where the four MERCOSUR countries have a positive trade balance with the EU. They therefore anticipate an increased economic potential from an opening up of European agricultural markets through a free trade agreement:

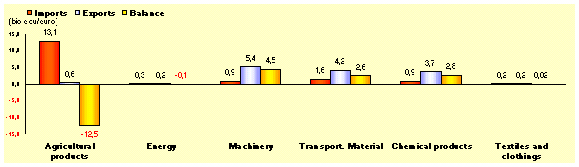

EU Merchandise Trade with MERCOSUR by product (2002):

Source: DG Trade: trade-info.cec.eu.int/doclib/html/111832.htm

In 2002 Paraguay had a surplus in the trade of agricultural products with the 15 EU countries of 78.7 million Euros, exporting goods worth 98.9 million Euro and importing agricultural products valued at 20.2 million Euros.[11] Argentina achieved a surplus of 4.6 billion Euro, from exports of 4.7 billion Euros and imports of 0.1 billion Euros.[12] Uruguay had a surplus of 0.3 billion Euros, exporting 0.4 billion Euros and importing 0.1 billion Euros [13], and Brazil attained a surplus of 7.4 billion Euros, with exports of 7.9 billion Euros and imports of 0.5 billion Euros.[14]

"While these treaties force developing countries to extensively open their markets for EU-products there are still high European tariff-barriers for agricultural goods which are also being produced in the EU. The FTAs with South Africa, Mexico and Chile furthermore include security clauses for the case that a rapid rise of trade flows threatens the overall economic situation of a partner – in reality this leaves a way out for the EU to close their markets temporarily if a southern partner achieves a successful increase of exports."[15]

Nevertheless, the four governments of the MERCOSUR agree that in the agricultural sector, for them the "central and essential" issue, success can be achieved. This, however, would require as a prerequisite "substantial concessions" from the EU negotiation team led by Karl Falkenberg.[16] Nonetheless, it should be mentioned that despite the priority that this interest is given, for example, by the strong Brazilian agricultural export lobby, one cannot assume a unified position of each particular government. Despite the expressed importance of the agricultural sector to the Brazilian government, even there, there are those with the opinion that the importance of the other issues of the marathon negotiations should not be neglected. Because of this there was a considerable amount of disagreement within the Brazilian government during the preparations of the FTAA-negotiation round from November 20-21, 2003.

The responsible authority on the Brazilian side for all internal MERCOSUR- as well as FTAA- and EU-MERCOSUR-negotiations is the Brazilian Foreign Ministry, Itamaraty, where the FTAA-negotiations are led by ambassador Samuel Pinheiro Guimarães. Guimarães is considered a general skeptic of the FTAA, while the Secretary of Agriculture, Roberto Rodrigues [17], and the Secretary of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade, Luiz Fernando Furlan, are seen as strong supporters who have openly criticized the negotiation strategy of Samuel Pinheiro Guimarães and have demanded more ways in which to influence the negotiation process for their ministries. The background to this is that "especially the Agricultural and the Development Ministries are considered strongholds of FTAA-apologists, because here the industrial lobbyists (from the agricultural, steel and textile sectors), which expect advantages from a free trade area, are very influential."[18] Therefore, Lula’s coalition government was obligated to cut the power of the Itamaraty in the area of free trade negotiations, by ordering the participation of the Agricultural and the Development Ministries, as well as the Finance Ministry of Secretary Antonio Palocci in the negotiations.[19]

The lobbyists of the agricultural exporters [20] are in favor of a broad free trade agreement with the EU, under the condition that all market-distorting agricultural subsidies are cut on the part of the EU: in 2003 Brazil was the world’s largest exporter of poultry in terms of net sales, exporting a value of 1.85 billion US-dollars compared to the U.S. with net sales of 1.5 billion US-dollars. However, in terms of quantity, the U.S. exported 2.3 million tons at an average price of 600 US-dollars per ton, as compared to Brazil that exported 2 million tons at a price of 900 US-dollars.[21] The current Secretary of Development and Foreign Trade, Luiz Fernando Furlan, was "Presidente do Conselho de Administração" ("Chairman of the Board") at Sadia S.A. before being appointed to office: "This Brazilian company is the largest producer of poultry, pork and processed meat in Brazil and is composed of 12 industrial plants, present in seven states." [22] This circumstance, according to a report by Anotícia (AN) from January 3, 2003, led an anonymous representative of the EU to come to the conclusion that Brazil, with this Secretary of State, will most likely act more radically in their law-suits concerning trade disputes in the area of poultry at the WTO arbitration court.[23]

One of the pending suits, raised by the Brazilian "Câmara de Comércio Exterior" (Camex) at the WTO on September 5th, concerns the increase in customs for Brazilian salted-poultry exports to the EU from 15 to 75 percent." Originally the European tariff for salted poultry from Brazil was lowered to 15 percent, as opposed to the higher tariff for frozen poultry. This led Brazilian exporters to rapidly salten their products in order to claim the lower tariff.[24] The EU responded with a counter-measure of increasing the tariffs to the level of frozen poultry.

It is currently unclear what will happen since the "failure" of Cancún to the peace clause for agricultural disputes within the WTO, which expires in 2004: A wave of lawsuits due to the broad agricultural export subsidies of the "North" cannot be ruled out, and their possible consequences for the negotiation process are hard to foresee.

Apart from being the world’s largest exporter of poultry, Brazil is also the world’s number one soya exporter: According to the estimates of Gazeta Mercantil, the 2003-2004 soya harvest produced 57 million tons, which would mean that Brazil would outstrip the U.S. as the world’s largest soya producer.[25] Brazil’s main trade partners are the states of the EU, which in November 2003 made up 33% of Brazil’s foreign trade.[26] – And soya and meat alongside with corn are those agricultural products that are of utmost importance in the negotiation process, not only with respect to the strategic economic interests, but also in view of the potential impact of a future free trade agreement between the EU and MERCOSUR. In this sense the already mentioned WWF-study judges that:

"In EU/MERCOSUR trade, the most environmentally sensitive crops at the present time are soy, corn and beef. The expansion of these crops threatens to accelerate deforestation, eliminate critical wildlife habitat and reduce biodiversity in ways that are irreversible. Some of these impacts are directly related to production practices and levels of production."[27]

MERCOSUR’s demands for reduced European agricultural subsidies, as well as for having market access, especially in the agrarian sector, are particular instances that have led to protests from the European agricultural lobby . The German Farmers’ Association (Deutscher Bauernverband), for example, published the following press statement on the occasion of the 5th WTO Ministerial Conference in Cancún:

"The German Farmers’ Association, in view of the inexorable process of globalization of the world economy, believes that binding rules in the trade of agricultural products are necessary. Fair rules of competition will lead to economic opportunities for German and European farmers as well as for farmers in all parts of the world, especially in the developing countries. Today Germany is already one of the largest importers of agricultural products and food. The German agricultural industry, however, also participates in international trade.

The German Farmers’ Association stands up for trade rules which in view of different development levels and values as well as different natural and climatic conditions enable an independent agricultural policy, but at the same time, if possible, are not trade-distorting."[28]

Along the same lines, the president of the European farmers’ association (COPA), Peter Gaemelke, told the magazine "The Economist" that the abolishment of agricultural subsidies does not constitute a "magic formula to end all evil in the world", but that rather agricultural support policies cannot be all equated and subsidies do not distort trade all to the same extent. The EU, according to Gaemelke, has reached advances with the reform of their joint agricultural policy, and now it would be the turn of others. In this sense "advanced developing countries like Brazil should stop hiding behind the real developing nations."[29]

The "agricultural question" divides the European countries, where on the one hand the French government sees itself in accord with the Irish and British governments, while the Portuguese, Spanish and German governments have opposing positions and interests: Already at the Ist Summit of Latin American, Caribbean and European Heads of State in Rio de Janeiro in 1999, the French government had used their veto against the EU-negotiation mandate on the fast opening of negotiations with MERCOSUR beginning January 1, 2001, in order to slow down the pace of the negotiation process.[30]

But apart from these differences between the European governments, the European Commission sees mutual advantages from an "Interregional Association Agreement" for the economy and development. The EU Commissary for Foreign Affairs, Chris Patten, expressed this during his speech at the BNC in November of 2000 in Brasilia in the following way:

"What is at stake in the negotiations between the EU and MERCOSUR is the possibility for a strategic, political and economic alliance between the only two real common markets in the world. The prospective association agreement will not only provide for short-term financial gains and closer political ties. It will create a free trade area covering nearly 600 million people. By doing this, it will generate democratic development, growing prosperity [...]" [31]

The accentuation of the "political-strategic partnership" between the EU and MERCOSUR is one of the main objectives of the EU-Commission, in part to distance itself from other "pure free trade agreements" that do not contain components on "dialogue" and "cooperation" in their negotiations on the mutual opening of markets. Concerning these issues the European Commission often appeals to facts like: "in 2000 and 2001 the EU participated with 38.5% of the total financial assistance to Latin America, the USA only with 27.2%." [32] Thereby it is overlooked that in Europe the share of public development aid as a percentage of GDP is currently only 0.37%, even though the industrial countries had accorded a target number of 0.7% of GDP at the UN Millenium Summit to halve poverty in 2000. But at the Monterrey Summit from March 18-22 they could just agree on a short-term increase to 0.39 percent. [33]

It therefore is not astonishing, that development-issues, as well as questions of cooperation and dialogue, are verbally present in the negotiation process, but that the emphasis of negotiation interests is rather placed on the area of trade matters. As a result voices from the civil society find the inclusion of development (or even sustainable development) in the negotiation process to be quite reserved:

"Negotiations of an interregional agreement between MERCOSUR and the European Union have been proceeding steadily since 1999. They include political and economic cooperation as well as trade. Given this broad remit it is extraordinary that issues relevant to the environment and sustainable development have barely been included thus far. An agreement that does not adequately cover the environment and sustainable development will have little credibility, either as an expression of current priorities or as an instrument for future cooperation." [34]

The author of this study reaches the conclusion, that this real absence of development and environmental issues on the part of the European Commission is also due to the institutionalized division: While, for example, within the EU international environmental matters fall into the competence of DG Environment (Directorate-General Environment), the EU-MERCOSUR negotiations lie in the hands of DG Relex (foreign policy) and DG Trade.[35] And in particular the interests of DG Trade naturally focus on trade and investment issues and not on social or environmental matters.

1.3 Trade – Development – Human Rights?

Since the passing of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights in Nice in December 2000, human rights have been a normative component of EU foreign and internal policy. Already since the 1990s the European Commission has integrated clauses into all bilateral trade and cooperation agreements with third countries, according to which mutual relations are based on the respect for and promotion of human rights and democratic principles. [36]

This so-called human rights clause was first mentioned in article 5 of the fourth Lomé-agreement with the ACP-states in December 1989. But even the EU foreign commissioner’s office hurries to admit:

"However, Article 5 of Lomé IV and similar articles in other agreements do not provide a clear legal basis to suspend or denounce agreements in cases of serious human rights violations or interruptions of democratic process.

It is for this reason that a clause defining democratic principles and human rights as an "essential element" of the agreements with Brazil, the Andean Pact countries, the Baltic States and Albania was introduced in 1992." [37]

Starting in 1992 human rights clauses were integrated into all agreements with third countries, which gave "a clear legal basis to suspend or denounce agreements in cases of serious human rights violations or interruptions of democratic process" to the EU.

Initially these "clauses" do not have the juridical status of an obligatory clause, but rather that of a declaration of intent. This is also the conclusion of Klaus Schilder from the non-governmental organization WEED:

"It therefore has to be feared that the EU will not convert questions of human rights and democracy into a central issue of the agreements, but rather to subordinate them to economic free trade-interests." [38]

In addition, even though these clauses are directed to all contracting parties, there is at the same time the suspicision that the EU negotiation side is more focused on the possibility of a unilateral threatening scenario on the part of the EU-Commission in order to "suspend trade oriented privileges" unilaterally in case of human rights violations of the contracting party – and least of all wants to see their own human rights policy monitored.

The Communication from the Commission, COM(1995)216 from May 1995 made the potential explosiveness of a general introduction of such human rights clauses evident: The DG Relex writes on its website that this Council Decision COM(1995)216:

"spells out the basic modalities of this clause, with the aim of ensuring consistency in the text used and its application. Since this Council decision of May 1995, the human rights clause has been included in all subsequently negotiated bilateral agreements of a general nature (excluding sectoral agreements on textiles, agricultural products, and so on). More than 20 such agreements have already been signed. These agreements come in addition to the more than 30 agreements negotiated before May 1995 which have a human rights clause not necessarily following the model launched in 1995." [39]

Most likely the European Commission became conscious of the fact that in view of the practices of European transnational companies, for example in the sweat-shop-industries of the textile sector or with respect to their own agricultural policy, it did not seem appropriate to include human rights clauses into agreements which cover these sectors. The danger of proclaiming the positive message of a non-sanctioning human rights "clause" within a broad partnership-agreement, however, did not seem to be all too latent.

In this sense article 1 of the agreement between the EU and Mexico on Economic Partnership, Political Coordination and Cooperation between the European Community and its Member States, of the one part, and the United Mexican States, of the other part, which was passed in 1997 and came into force in October 2000, solemnly explains the so-called human rights and democracy clause:

"Article 1

Basis of the Agreement

Respect for democratic principles and fundamental human rights, proclaimed by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, underpins the domestic and external policies of both Parties and constitutes an essential element of this Agreement." [40]

In the same way the agreement between the EU and Chile, passed on November 18, 2002 and ratified in February 2003, also states in article 1:

"Article 1

Principles

Respect for democratic principles and fundamental human rights as laid down in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and for the principle of the rule of law underpins the internal and international policies of the Parties and constitutes an essential element of this Agreement." [41]

This democracy and human rights clause will also be an integral component of the planned "Interregional Association Agreement" between the EU and MERCOSUR.

"The aim of the SIA, which is very much at the cutting-edge of the field of impact assessment, is to assess the impact that the results of trade negotiations will have on sustainability." [42]

In this way the EU, by means of the DG Trade, financed its SIA-series which included a "Methodological Study" and a "Sustainability Impact Assessment of Proposed WTO Multilateral Trade Negotiations," both prepared by the University of Manchester, a "Sectoral SIA on Food Crops Sector" prepared by the Stockholm Environment Institute, a "SIA on EU - A.C.P trade negotiations" as well as "SIA on EU - GCC trade negotiations", both prepared by PriceWaterhouseCoopers, and a "SIA on EU - MERCOSUR / Chile trade negotiations" by Planistat Luxembourg. [43]

The SIA of Planistat Luxembourg was meant to investigate the potential impact and dangers of the free trade agreements between the EU and Chile as well the EU and MERCOSUR, in two steps: First by means of a methodological assessment and then through an actual impact study. The EU-Chile agreement was investigated first and the study was concluded with a Final Report in October 2002. The SIA on the EU-MERCOSUR agreement, however, did not get any further than the draft inception report of February 2003; the revised version should have been published in June 2003. At the same time the solemn intention of this SIA on EU-Chile/MERCOSUR was in the beginning not less than:

"to provide a better basis than has existed to date for EC institutions to shape any sustainability-related aspects of the EC approach to these negotiations, to provide an SIA-based assessment of negotiation underway and a review of the results of negotiations when the time comes to present them for formal adoption." [44]

And the EU foreign trade commissioner, Pascal Lamy, had stated in a speech on February 6, 2003 in Brussels, at a seminary on new approaches to assess the impact of free trade agreements:

"If trade is to be a tool for development, we need to ensure that it is compatible with sensitive management of the environment and social development. SIAs are an essential means to help us achieve these challenges." [45]

Already in April 2002 a study prepared by order of the WWF on the Sustainable Impact Assessment EU/MERCOSUR judged that:

"In accordance with its announced policy, the Commission is preparing to undertake a sustainability assessment of the EU/MERCOSUR negotiations. That is a welcome development and one that may help to identify some of the missing elements of the current agenda. In principle, however, a sustainability assessment is not designed to rectify a negotiating agenda that is inadequate, in particular when its shortcoming concern primarily political issues and missed opportunities. It is difficult to see what a sustainability assessment can contribute to negotiations that have already been under way for three years under an agenda that takes little or no account of the issues surrounding sustainability." [46]

During the course of 2003 the Eurostat-scandal became publicly known, with Planistat Luxembourg at its center: Planistat had created a bank account for presumed irregular reserves (the investigations of the public prosecutor are still running) under the self-explanatory name "Euro-Diff", so that the EU-Commission saw itself obligated to cancel all contracts with Planistat, which included the SIA on EU-Chile/MERCOSUR.[47]

One of the first consequences of this was that the Planistat-website (http://www.planistat.com) published a memorandum:

"Suite à une décision de la Commission Européenne, ce site n’est plus mis à jour depuis le 10 Juillet 2003.

Following a decision of the European Commission, this website was not updated since the 10th of July 2003.

De acuerdo a una decisión de la Comisión Europea, esta página web no ha sido actualizada desde el 10 de julio de 2003",

before the website was completely removed from the web, - and the staff was fired. The workers union OGB-L, Onofhängege Gewerkschaftsbond Lëtzebuerg, demanded that "the creation of social compensation plans cannot be the solution to iron out the errors of the EU-Commission." [48] It was above all the europarliamentarian Herbert Boesch (SPÖ, MEP), who tried to clarify the EU-Commission’s possible responsibilities within the Eurostat-Planistat-scandal with his persistent investigations. Among other things he initiated the "Written Inquiry to the Commission. Commercial Relations of the Commission with the Planistat Group" on May 19, 2003. [49] Meanwhile a new invitation to tender for the SIA EU-MERCOSUR study was announced on October 21, 2003: "B-Brussels: framework contract to provide a sustainability impact assessment (SIA) of EU-MERCOSUR negotiations and a preliminary ex-post assessment of EU-Chile negotiations C398 - Invitation to tender." [50] This new SIA is supposed to devote itself anew to a broad assessment of the possible impact of the EU-MERCOSUR free trade agreement. It can only be hoped that no new unpleasant oddities will ocurr, under which things like the following will have to be read:

"In summer [2002, author’s note] the preliminary results [of the SIA Chile-EU, author’s note] were presented to invited representatives of the so-called civil society in Brussels. On this occasion the representative of the Commission instructed the authors of the study to omit the pages on expected job-losses in the final version of the study. During the mentioned Chile-session of the European Parliament the Commission was asked and contrary to expectations did not deny the embarrassing incident. It was explained that the found job-losses were small, and that predictions of the future often brought results which could not be confirmed by reality." [51]

If the significance of the SIA can be handeled in this way, it can be speculated that in other areas the EU-Commission might not be too particular about its own pretensions either.

"The objective of Community development co-operation policy is to foster sustainable development designed to eradicate poverty in developing countries and to integrate them into the world economy. This can only be achieved by pursuing policies that promote the consolidation of democracy, the rule of law, good governance and the respect for human rights." [52]

If human rights, the rule of law, democracy and sustainable development build the framework for the guidelines and objectives of development policy of the EU, then it has to be asked, how the EU-Commission’s triad composed of foreign trade, foreign policy and development policy can be harmonized. In the same way it should be asked how such normative statements like that of the human rights clause contained in a EU-MERCOSUR free trade agreement can be put into practice and how it can be supervised: It is indeed questionable, how the noble claim of human rights in its broadest form can be harmonized – given the reality of a competitive global economy - with a free trade agreement, which in its most basic configuration aims to liberalize trade, investment and capital flows, to open markets, and liberalize the service market for public goods as well as for government procurement.

The issue of human rights will be explicitly mentioned in the proposed agreement, following the model EU-Mexico and EU-Chile. According to the EU Commissioner in charge of External Relations, Chris Patten, the proposed "Interregional Association Agreement" between the EU and MERCOSUR should combine trade and development in a way that would permit the evolution – in a dynamic process – of democracy and human rights.

[Continuation of the quotation by Chris Patten]

"It will create a free trade area covering nearly 600 million people. By doing this, it will generate democratic development, growing prosperity and respect of human rights. Where prosperity reigns, democracy and human rights can take firm root. [...] We are seeking a wide political and economic partnership, building on our common commitment to liberty, democracy, respect for human rights, fundamental freedoms, the rule of law and sustainable development." [53]

Contrary to these kinds of pompous and at the same time magical prophecies, now and then even European government representatives prefer verbal skepticism:

"Also within the EU, a lot has to be done in terms of coherence, given the fact that there are still large contradictions between EU trade policy, EU agricultural policy and EU development policy." [54]

The social problems, for example, resulting from European agricultural policy for millions of small farmers in the countries of the South are well known, have been studied and have been the object of large campaigns by civil society: As for example the problems, risks and consequences of the WTO negotiations on services (GATS) and the privatization and commercialization of public goods or as another example the negotiations for a Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI) within the framework of the OECD (1998) and the campaign preceding the 5th WTO Ministerial Conference in Cancún, Mexico during the year 2003.

The investment-issue is, among other topics, also on the agenda of free trade negotiations between the EU and MERCOSUR:

"As always, investment negotiations have major implications for the environment and sustainable development. Investment is the only tool that can reliably shift currently unsustainable economies towards more sustainable practices. At the same time, international investment agreements have proven themselves to be potential obstacles to the ability of governments to adopt measures that are needed to promote sustainability. The EU/MERCOSUR investment negotiations must be monitored from the perspective of the environment and sustainable development." [55]

Will there be a final conclusion on investment within the EU-MERCOSUR free trade negotiations? Will there be some kind of "trade off" between the negotiation partners, e.g., concessions of the Europeans in the agricultural area – the abolishment or reduction of agricultural subsidies and the suspension of import-quotas – against MERCOSUR’s concessions in the areas of investment and government procurement? Would the expected macroeconomic gains of MERCOSUR countries in the agricultural sector compensate the expected set-backs in the areas of investment, free capital flows and public procurement? Or is the investment issue just used as a pretext by the Europeans in order to trade it generously against the concessions made by MERCOSUR to avoid the agricultural issue? Should the investment demands of the EU in this sense just be an object of negotiation in the bid for other issues, i.e.: "A bone thrown to the dogs?" [56]

Chapter 2:Foreign direct investmentas the object of international trade regimes

2.1 Foreign direct investment: An opportunity for development and human rights?

Foreign investment by definition can be split up into portfolio-investment and direct investment. Foreign portfolio-investment is defined as capital investment like bonds, stocks, investment-fund shares, etc., made from abroad, such that due to its minority share (less than 10% of the total value) it has no substantial influence on the management or the company as a whole. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is defined by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) as:

"[...] an investment involving a long-term relationship and reflecting a lasting interest and control by a resident entity in one economy (foreign direct investor or parent enterprise) in an enterprise resident in an economy other than that of the foreign direct investor (FDI enterprise or affiliate enterprise or foreign affiliate). FDI implies that the investor exerts a significant degree of influence on the management of the enterprise resident in the other economy. [...] FDI may be undertaken by individuals as well as business entities." [57]

Foreign Direct Investment Flows [58], are defined by the UNCTAD as:

"Flows of FDI comprises capital provided (either directly or through other related enterprises) by a foreign direct investor to an FDI enterprise, or capital received from an FDI enterprise by a foreign direct investor. FDI has three components: equity capital, reinvested earnings and intra-company loans." [59]

Foreign Direct Investment Stock [60] is defined as:

"FDI stock is the value of the share of their capital and reserves (including retained profits) attributable to the parent enterprise, plus the net indebtedness of affiliates to the parent enterprise." [61]

Furthermore, a distinction can be made between a so-called Greenfield-Investment, i.e., the realization of a new investment, and the area of Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A), which refers to take-overs of already existing investments. According to KPMG Corporate Finance, the value of global company transactions fell by almost 50% in 2002 as compared to the previous year, reaching 996 billion US-dollars, while in 2000 the value of worldwide Mergers and Acquisitions had been substantially more than 3 trillion US-dollars, thereby accounting for by far the largest share of FDI-Flows. [62]

The "World Investment Report 2003 - FDI Policies for Development: National and International Perspectives" of the UNCTAD [63] also complained about the worldwide decrease in FDI-Flows from "$1.4 trillion in 2000 to $650 billion in 2002, raising considerable concerns about prospects for achieving the Millenium Development Goals," [64] in numbers: from 1,400,000,000,000 in 2000 to 650,000,000,000 in 2002. Latin America, according to the World Investment Report 2003, accounted for 56 billion US-dollars of FDI-Flows in 2002. This corresponds to the lowest level since 1996. The decrease of investment flows occurred especially in the services area (telecommunications and banking sector) in Argentina, Brazil and Chile. [65]

The years 1996 to 2000 recorded a worldwide boom in cross-border investment flows. A large part of these FDI flows, however, were Mergers & Acquisitions and not Greenfield-Investment, so that the exploding capital flows between 1996 and 2000 can be explained by the hysterical wave of M&A at the end of the nineties, which in Latin America also coincided with privatization and neoliberal market-opening policies in entire economic sectors, which were pushed forward by the IMF and the World Bank and were accompanied by serious social problems for the population of the respective countries.

These developments, however, did not stop the authors of the UNCTAD’s World Investment Report from complaining about the decrease between 2000 and 2002, nor from creating a central measure out of the boom, which turned out to be a bubble and was unproductive in terms of solemn development objectives: They [the authors of the UNCTAD’s World Investment Report] affirm that the decrease of these investment-flows would be "raising considerable concerns about prospects for achieving the Millenium Development Goals" [66] - as if flourishing international capital transaction would constitute a condition and especially a guarantee for development.

These Millenium Development Goals, passed by the General Assembly of the United Nations in September 2000 [67] are to:

1. Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

2. Achieve universal primary education

3. Promote gender equality and empower women

4. Reduce child mortality

5. Improve maternal health

6. Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases

7. Ensure environmental sustainability

8. Develop a global partnership for development

All UN member states have committed themselves to reach these goals by 2015.

But what are these supposed connections between FDI-Flows and these Millenium Development Goals – that are viewed as immanent by the authors of the UNCTAD-study? They associate some kind of magical relationship of foreign private investment and development, so that, e.g.:

• Foreign private investment in the food industry would eradicate hunger.

• Privately financed primary schools would guarantee a universal primary education for all children.

• Sales-related production of goods and services would promote gender equality and the empowerment of women.

• Privately financed hospitals, a competitive health sector and profit-oriented pharmaceutical research would reduce infant mortality, improve maternal health and combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases.

• Privately financed industry and infrastructure projects would ensure environmental sustainability and develop a global partnership for development.

The reasons for propagating this connection and what it seems to actually mean can be extracted from the foreword of the "World Investment Report 2003 - FDI Policies for Development: National and International Perspectives": "UNCTAD seeks to further the understanding of the nature of transnational corporations and their contribution to development and to create an enabling environment for international investment and enterprise development," [68] - it can hardly be expressed more clearly whose "environment" and "development" is meant.

Behind this lies the firm belief that 1) it is the market and only the market that constitutes the universal remedy for development and the belief that 2) foreign direct investment plays a special role in this context, as if each had a direct impact on the corresponding development of the investment-importing country: Job-creation, the extension of infrastructure, technology-transfers, stabilization, the creation or stimulation of national value creation chains, the stimulation of domestic demand, in order to, in the end, foster development.

1) It is on the one hand questionable, to what extent this one-way causation determined connection between market and development should promote something like sustainable development. The Brundtland-Report ("Our Common Future") of the Worldcommission on Environment and Development from 1987 had defined sustainable development as follows: "Sustainable development is development, which satisfies the needs of the present generation, without limiting the capability of future generations, to satisfy their own needs." Furthermore, it can be questioned how this connecton should promote development– here in terms of the more narrow definition of mere growth – at all, even in view of the above mentioned UN Millenium Goals, since the neoliberal understanding of market and development assumes – unquestioned – that development occurs –exclusively- by means of the market. Not only market access in the area of foreign trade is demanded, but simply everything is to be left to the market: National or regional measures like programs to promote development or governmental incentives to create or implement socially or ecologically meaningful objectives are not only not regarded by the neoliberal model, but are explicitly contrary to this. If everything is subordinated to the regime of production and profit, then the governmental scope for design and action and thereby also democratic decision-making processes are severely limited.

2) It is also questionable in terms of macroeconomics, how cause and effect – with respect to the relationship between FDI and development - should work in the desired way: It is not inevitably causal, that FDI is directed towards the respective domestic market and thereby would be able to give impulses to promote development. Especially during the last years, and particularly under the pressure of the requirements that IMF has placed on debtor countries, the highly indebted Latin American countries have seen themselves in the macroeconomic obligation to realize export-surpluses, so that inflowing foreign currency has to be largely targeted towards exports. With regards to Brazil or Argentina, for example, the following macroeconomic image can be drawn: Foreign direct investment increasingly brought foreign currency into the country during the nineties, but this direct investment will, on the one hand, lead to faster outflow of profits: Even though a direct investment in the short term has a positive influence on the balance of payments, in the long run it has the disadvantage of creating capital outflows. On the other hand, this direct investment will not create further foreign currency inflows, as it is predominantly focused on the domestic market – which for both countries is especially problematic considering their high foreign debt and in this respect cannot contribute to macroeconomic stabilization against potential financial crises. Additionally, even though the by far largest part of this direct investment is directed towards the domestic market, it is particularly concentrated in the area of services like telecommunications and banking: How can such direct investment, which is targeted at the domestic market, then have the ability to promote regional development? Argentina and Brazil are confronted with the dilemma of having to attract direct investment in order to pay off their debts and to maintain good balance of payments– and on the other hand, trying to use this foreign capital in a way which is productive for regional development, i.e., directed towards the domestic market. Whether the telecommunications and banking sectors can be regarded as especially productive in this sense, can be seriously doubted.

Furthermore, it is not quite understandable why one should expect a drive for (sustainable) development from investors, who function according to the market laws of profit and performance, cost reduction and ousting of the competition. Since it is not expected from the market participants that the investments undertaken be directly utilized for socially and environmentally friendly development, the indirect connections of the neoliberal development theories are used to support the argumentation that: According to this development-model the decisive agent is not the state, but the free forces of the deregulated market which will with the "invisible hand" bring about the promotion of development.

Worldwide countries adhere to this strong belief in the market, that foreign investment will lead to development: there is increasing competition between states for foreign investment, which is expressed in national, regional and local programs for the promotion of FDI, i.e., in preferential tax treatment for private foreign investors. It should be mentioned here that – even thinking in terms of market-rules-

• according to a study conducted by the consulting firm McKinsey [69] governmental investment incentives are "harmful": The study reaches the conclusion, that governmental investment incentives lead to a decrease in productivity, to no creation of new jobs, as well as to a reduction in the amount of foreign investment, which would have been made anyway in the absence of incentives. [70]

• according to a study of the Ifo-Institute, which investigated the case of the Federal Republic of Germany, 90 percent of foreign investment was made to assure sales abroad and thereby primarily served the investment-exporting country [71] in order to maintain employment "at home", as in the case of Germany, where 1/3 of employment depends on exports and where the connection between foreign investment and internal economic power has to be regarded in a different light.

• Once again the question arrises whether FDI is conducive to sustainable development in the proposed manner (or if it does so at all).

"only 2.89 percent of their resources for production and packing material in Mexico. In constrast the Mexican manufacturing industry, which is not part of the maquila-industry, still had in 1983 acquired 91% of its production resources internally, in 1997 it was only 37%. Additionally, most foreign investment in Mexico concentrates on this highly export-oriented sector. In short: We export a lot, but our exports are not particularly Mexican." [74]

According to the Mexican economist Alberto Arroyo, as a consequence of NAFTA "production chains were dissolved and production sites denationalized." [75]

Although during the first 8 years of NAFTA until 2002 Mexico had received 140 billion US-dollars in foreign investment, the majority of this inflow of investment capital was appointed to M&A of existing firms and on top of that jobs were lost in the national supplier’s chain. And the supposedly so successful maquila-industry has in fact created jobs, but these jobs are:

"insecure and based on fixed-term contracts with long working hours and the organization in unions is prevented by strong and illegal means of exerting pressure. Additionally these jobs are highly dependent on the economic cycle in the U.S. From November 2000 to March 2002 the U.S.A. was struggling with serious economic problems, and 287,630 jobs were cut in the maquila-industry, somewhat less than half of the employment created in this sector during the first seven years of NAFTA." [76]

Therefore, the connection, which is determined within the neoliberal consensus, of the opening of markets, of FDI and of regional, national or even overall development is anything but proven. Furthermore, this market supported association between FDI and the direct impact on development of the investment-importing country, like job creation, the extension of infrastructure, technological transfers, stabilization, the creation or stimulation of national value creation chains and the promotion of domestic demand, in order to promote development, remains to be an illusion , and the supporters of this market approach continue to give vague answers when inquired about its origin.

Besides this, there are many more far-reaching opinions on the impact of FDI. The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights has stated in her report on "Human rights, trade and investment - Sub-Commission on Human Rights resolution 2002/11" that:

"Concerned that international economic law and human rights law have developed as two parallel and separate regimes, with the risk that human rights principles, instruments and mechanisms will be marginalized as highlighted by the actual or potential human rights implications of World Trade Organization agreements, including the General Agreement on Trade in Services, the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights and the Agreement on Agriculture,[...]

Considering that when not carefully regulated, foreign direct investment - as a key element of the globalization process, one of the main modes of delivering trade in services and a central activity of transnational corporations - can have a detrimental effect with regard to the enjoyment of human rights,

Noting that the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, in her report on liberalization of trade in services and human rights (E/CN.4/Sub.2/2002/9) [77], has identified investment as the most problematic mode of trade in services from the perspective of human rights,[...]

Reaffirms the importance and relevance of human rights obligations in all areas of governance and development, including international and regional trade, investment, and financial agreements, policies and practices, and renews its request to all Governments and economic policy forums, including the World Trade Organization, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, to take international human rights obligations and principles fully into account in international economic policy formulation and implementation; [...]" [78]

Here the issue is not about comprehending foreign capital per se as bad as compared to "good national capital", rather its about the question of to what extent foreign capital operates in a dubious manner with respect to social, environmental and human rights: Are transnational corporations "out of control" [79] due to not only their size, which in some cases exceeds the GDP of entire countries, but also to the nonexistence or insufficient internationally valid and concrete juridical obligations in international treaties? Are they in the end better off than domestic companies, due to international treaties that regulate their rights, but not their obligations? Is national jurisdiction being hollowed out and surpassed by international treaties on investment protection? Are transnational companies problematic due to their actions, their globally-optimizing pure profit orientation and their mere size? And finally: What role can international treaties and agreements between states have that focus on foreign investment?

2.2 International Agreements and Treaties on Investment

International negotiations on investment agreements can be conducted between two states (bilaterally) in form of a bilateral investment agreement (BIT), between two regional blocks (a special case of bilateralism: bi- or interregional) as part of a broader free trade agreement (FTA), among several states within the framework of a superior international organization valid for some member states (plurilateral), or among all member states (multilateral). Negotiations on investment agreements deal in general with the basic stipulations for cross-border investment.

Bilateral treaties between states whose main focus lie on cross-border investment exist since the "Treaty of Amity, Commerce and Navigation", the so-called "Jay-Treaty" which was signed in 1794 between "His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America", ratified in 1795 and publicly proclaimed at the beginning of 1796. This treaty was the first to introduce arbitration courts ("commissions") as a bilateral mechanism to solve disputes. [80] The first bilateral investment agreement, in the modern sense, was concluded in 1959 between Pakistan and the Federal Republic of Germany. [81] Today a large number of bilateral agreements exist (in September 2002 an estimated 2000 bilateral agreements were in force globally) [82].

Modern bilateral investment agreements are similar in content and are all oriented towards equal market access rules, reciprocal treatment according to the principles of "non-discrimination" contained in the MFN clause and the National Treatment Clause, guarantees for capital and profit transfers and arbitration mechanisms:

"Modern BITs have retained broad uniformity in their provisions. In addition to determining the scope of application of the treaty, that is, the investments and investors covered by it, virtually all bilateral investment treaties cover four substantive areas: admission, treatment, expropriation and the settlement of disputes. Almost all modern BITs include provisions dealing with disputes between one of the parties and investors having the nationality of the other party. In this respect most provide for arbitration under the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States (the ICSID Convention) which entered into force in 1966." [83]

They thereby vary partially in their definition of the term investment: The "more narrow" definition only comprehends direct investment, while the "wider" one also contains portfolio investment. But no investment agreement makes a distinction or explicitly mentions "socially productive capital". The term "expropriation" in most agreements follows the "wider" meaning of direct expropriation and equivalent measures.

Besides these bilateral investment agreements, which explicitly focus on the area of investment, the investment issue may also be a component of broader free trade agreements, as for example the "Association Agreement" between the EU and Mexico ("Global Agreement"), which was signed in 1997 and entered into force in October 2000, as well as the agreement between Chile and the EU, which was signed in November 2002 and entered into force in February 2003. On a plurilateral or multilateral level several negotiation rounds on multilateral or international investment agreements have taken place, which were in part ratified, like the plurilateral TRIMs-agreement within the WTO, and which in part failed, like the multilateral MAI within the OECD in 1998 or the (provisional) failure of the Doha Development Agenda of the WTO (see below).

Continuous demands from trade and industry for international investment regulations in the form of bilateral investment agreements or embedded into free trade agreements consistently put the investment issue onto the political agenda. Foreign investors thereby chiefly prioritize the issues of investors’ rights like investment protection and legal security, market access and national treatment, as well as free capital transfer. For this reason, it is predominantly the FDI-exporting countries which speak out for a regulatory framework on an international level. The standard formulation with only small differences in formulations reads as follows:

"to secure transparent, stable and predictable conditions for long-term cross-border investment, particularly foreign direct investment". [84]

The issue of cross-border investment (along with the agricultural market, subsidies, services, intellectual property rights) is one of the central and most disputed topics in the current negotiations on bilateral and multilateral free trade agreements. The free trade negotiations in the framework of FTAA/ALCA, the large Free Trade Area of the Americas planned for 2005, and also the free trade negotiations between the EU and MERCOSUR explicitly refer to the "multilateral" framework of negotiations within the World Trade Organization (WTO).

2.3 The World Trade Organization WTO

Within the World Trade Organization negotiations take place on the extensive "liberalization" of markets. In 1995 the GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) was replaced by the WTO. According to the WTO’s portrayal of itself, it sees itself as

"a rules-based, member-driven organization — all decisions are made by the member governments, and the rules are the outcome of negotiations among members" [85],

"The World Trade Organization (WTO) is the only global international organization dealing with the rules of trade between nations" [86].

Furthermore, it is stated that:

"The WTO is GATT plus a lot more. [...] GATT deals only with trade in goods. The WTO Agreements now cover services and intellectual property as well." [87]

In the multilateral negotiations of the WTO the representatives of member states negotiate as contracting parties of the WTO, - in the case of EU member states, however, this function is centrally exerted by the European Union (the EU-trade-commissioner, currently Pascal Lamy). According to article 133 of the EU-founding Maastricht-Treaty the EU-trade policy is expressedly part of EU-sovereignty. The same is valid for association treaties (article 310). According to the Amsterdam-Treaty, article 133 was modified so that by a unanimous decision the joint trade policy, which is exerted by DG Trade, can be extended to international agreements and treaties on services and intellectual property rights. [88] This means that the negotiation-authority in issues of foreign trade, like bilateral or WTO-negotiations, lies primarily within the respective EU-commissioner’s office.

The decisions made within the WTO on the central issues of international trade are ultimately binding. Once a WTO-member state has accepted the respective rules, there are no further possibilities to make changes: it is a one-way street. [89]

2.3.1 WTO rules

The reciprocal WTO-rules of the Most Favored Nation Clause and the National Treatment Clause are applied to all free trade agreements, as well as bilateral investment agreements. The cross-border design of market access, according to the principles of non-discrimination of the

• Most Favored Nation Clause ("most favored nation treatment": no less favorable than the treatment granted to any other country) and the

• National Treatment Clause ("national treatment: giving others the same treatment as one’s own nationals. Treating foreigners and locals equally") [90], is supposed to give foreign suppliers from all countries the same opportunities as domestic suppliers.

This, according to the ideas of the WTO, should affect all areas of trade as defined by the WTO, i.e., the area of goods (GATT), services (GATS) as well as the trade-relevant area of intellectual property rights (TRIPS). The GATT-treaty is a so-called "top-down" agreement, which means that the rules are automatically valid for all member states, except for the case that a country has been able to explicitly exclude certain areas in form of so-called "negative sectors lists." The GATS agreement is a so-called "bottom-up" agreement, according to which only those areas are affected by the accorded rules, which appear in the "list of commitments," the so-called "positive sectors lists." Investment issues affect the areas of goods (GATT) as well as services (GATS), and according to the WTO can be classified within the topic of "trade and investment" and divided into three levels:

• The TRIMs agreement [91] (investment in the goods sector)

• The GATS agreement [92] (investment in the services sector is one of four areas treated by GATS)

• Relationships of "trade and investment" [93] is one of the so-called Singapore Issues [94] on the WTO-agenda since 1996. The "new issues" established at the WTO Ministerial Conference in Singapore are:

• trade and investment

• competition policy

• government procurement

• and trade facilitation.

2.3.2 The TRIMs agreement

The TRIMs agreement ("Agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures") [95] was passed during the GATT Uruguay Round in 1994 and constitutes one of the foundations of the WTO that was founded in January 1995. It recognizes certain asymmetries to the effect that some transition periods were granted, in order to put international agreements into practice. This agreement defines the treatment of investment in the goods sector and not investment in the services sector (which is regulated by GATS). The TRIMs agreement deals with "trade-related investment measures of member states," which in a broad sense affects domestic and foreign investment. The 5 pages of the treaty do not give an exact definition of the term "trade-related investment measure," but instead list in the annex the particular types of laws, rules and guidelines that are to be considered as relevant for trade with respect to investment. [96]

The TRIMs agreement follows the WTO principle of so-called "National Treatment", according to which every foreign investor should be granted the same conditions as domestic investors. If state regulations should demand any kind of requirements, so-called "performance requirements" or "local content rules," from investors, for example, by passing regulations which demand a fixed percentage of local, regional or national suppliers or shareholders (so-called "joint ventures") or by implementing minimum –percentage -requirements to employ domestic workers, this would violate the "National Treatment" principle.

If according to a WTO member state another WTO member violates the rules of the agreement, legal action can be taken within the WTO. Any legal action can only be undertaken by one government against another, private investors cannot do this (see the chapter on NAFTA), nonetheless they can convince their respective government to do so. But for some industrialized countries, this agreement does not reach far enough, so that several intents were made (Multilateral Agreement on Investment, MAI, in the OECD, which failed under the pressure of the NGOs and civil society in 1998) and are being made in order to implement further reaching cross-country regulations.

2.3.3 The GATS agreement

The General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) [97] is dedicated to the area of services in its four trade-relevant facets ("Four Modes"):

1. Cross-border supply, e.g,. international phone calls,

2. Consumption abroad, e.g., tourism,

3. Commercial presence, e.g,. the opening of a bank branch, where "commercial presence" refers to the topic of "trade and investment" as a partial area of services,

4. Presence of natural persons, i.e., the cross-border supply of services by individuals.

The General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) was integrated into the articles of incorporation of the WTO in 1995, and the GATS negotiations should be newly regulated and completed by the time the current world trade round (Doha –Development Round, DDR) reaches its conclusion in 2005. The GATS defines services in a very general manner, which therefore also includes issues, which in many countries are of public domain: Education and healthcare, postal services and telecommunications, public infrastructure, the supply of energy and water and cultural and social work. [98]

The GATS regulations stipulate that the entire area of services is to be subjected to a standardized global set of rules. Thereby, the GATS adheres to the WTO non-discrimination-guidelines of equal market access for all domestic and foreign suppliers according to the principles of "National Treatment" and "Most Favored Nation" and grants the opportunity for legal actions at the WTO arbitration court if these guidelines are infringed upon.

Public procurement–processes, according to the NT principle, are no longer allowed by law to give preferential treatment to local suppliers and producers ("local content"). A country which has signed the agreement can, according to the Mode 3 of GATS ("commercial presence", cross-border supply of services), no longer make any so-called "performance requirements" of foreign investors (like, e.g., the minimum percentage requirement for employing the local workforce or for technology transfers). Even environmental and social regulations of each member state run the risk of infringing upon the NT principle.

In contrast to the GATT treaty, which was a so-called "top-down" agreement (i.e., the rules apply automatically to all member states unless a country has explicitly negotiated exceptions for some sectors in the form of so-called negative lists), the GATS is a so-called "bottom-up" agreement (the rules apply if they appear in the so-called "list of commitments" of the respective country). It is in particular this "bottom-up"mechanism, which the WTO commonly quotes as an argument for the democratic legitimacy of GATS: Democratically elected governments would in the end decide which sectors in their country would be assigned to GATS and which would remain under national sovereignty, i.e., "in the exercise of governmental authority." [99]

The problem in this case is the unclear definition of "in the exercise of governmental authority" and secondly, the fact that everytime a (domestic or foreign) private supplier competes with public services, the set of regulations under GATS can be applied and with it the possibility of a legal complaint before the WTO arbitration court.

Considering the rules under GATS, the danger exists, for example, in the case of education, that a private school, which is mainly owned by a foreign investor, could take legal action against the "market-distorting subsidies" of a neighboring public school, even if the educational sector was explicitly excluded in the form of a negative sector list: Even if the sovereignty clause within the GATS applies:

"Article I(3) of the GATS excludes "services supplied in the exercise of governmental authority". These are services that are supplied neither on a commercial basis nor in competition with other suppliers. Cases in point are social security schemes and any other public service, such as health or education, that is provided at non-market conditions." [100]

The formulation "neither on a commercial basis nor in competition with other suppliers" [101] is quite dubious. If a private school, mainly owned by a foreign investor, which works on a profit-basis, sees itself in competition with a public (non-profit) school, this private school would theoretically be able to take legal action against the public school, i.e., against the educational system as a public good in general. In the end – as no state will be able to abolish all subsidies for public schooling - this might lead to the situation of private schools obtaining the same right to state-subsidies as public ones. [102]

This would mean submitting public services to commercial interests through the GATS - which would have enormous consequences for social, cultural and human rights.

2.3.4 The Relationships of "Trade and Investment"

Since 1996 there have been working-committees within the WTO who have been debating the issues pertaining to "trade and investment." [103] The objective of these committees is to elaborate and pass a multilateral framework agreement, which should establish rules on investment in all its facets for all WTO member states. The aims of the so-called Doha Agenda for the area of "trade and investment" range from identifying the comprehensive scope of application and definition of the term investment, of transparency, of non-discrimination, of the MFN and NT clauses, of rules for "pre-establishment" on the basis of GATS-definitions, to positive-sector lists, concessions on development-issues, as well as defined exceptions and predetermined safeguard clauses for balance of payment crises, as well as a dispute-settlement mechanism. [104]

In November 2001 the 4th Ministerial Conference of the WTO in Doha, Qatar, decided that negotiations on a

"multilateral framework to secure transparent, stable and predictable conditions for long-term cross-border investment, particularly foreign direct investment" (§20 Ministerial Declaration, 14.11.2001, Doha) [105]

should only be initiated on the basis of a consensual decision on the modalities of negotiations which were to be treated at the 5th Ministerial Conference in Cancún from September 10-14, 2003:

"[W]e agree that negotiations will take place after the Fifth Session of the Ministerial Conference on the basis of a decision to be taken, by explicit consensus, at that session on modalities of negotiation." (ibid.).

First the "modalities of negotiations" were to be defined "by explicit consensus" and after Cancún the negotiations could have started.

According to the chairman of the Ministerial Conference the formulation "by explicit consensus" left a wide margin not only to debate "how" to negotiate, but also to pose the general question if negotiations should take place at all. Nevertheless, the Ministerial Declaration defined the establishment and desired conclusion of the negotiations as having already been determined, since the deadline for the conclusion of the negotiation round on investment had already been set by them to be:

"deadline: by 1 January 2005".

The decision to begin negotiations on a future investment agreement within the WTO was thus not already made in Doha, as the EU had, for example, constantly repeated. This decision depended on the potential agreement in Cancún on the modalities and the content of the negotiations. And this decision never materialized: Cancún "failed".

Numerous articles haunted the world press in the days after the 5th Ministerial Conference which ascribed the preliminary failure of the Doha Agenda in Cancún to the irreconcilable contradictions between the states of the North, who insisted on subsidies for their domestic agricultural markets and exports, and the states of the South, who were up in arms against these subsidies which rob the basis of livelihood from millions of agricultural workers through this subsidized price dumping.

Many speculations on the reasons for the break down in Cancún arose, e.g., that some delegations recognized earlier than the European delegation, led by Trade Commissioner Lamy, that due to the disputed agricultural question no agreement would be reached, so that it would be better to induce an early failure at a time when the negotiations on the sensible agricultural issue had not yet started and the also heavily disputed Singapore issues, like investment, public procurement, competition policy and trade facilitation were on the agenda. As the European Union is one of the main advocates of these "new issues" - even though the EU in Cancún, after having encountered a strong, resistance finally managed to take back the issues of investment and competition policy in order to maintain at any cost the issues of public procurement and trade facilitation on the agenda – the guilty states could be found among those, who, like the EU, insistently wanted to negotiate the – even though reduced – Singapore issues, before discussing the agricultural issue. Another version is obviously the one of the EU –trade –delegation, which wanted to put the blame for the failure of the negotiations on the G-20 countries, which were formed in Cancún.

The "failure" of Cancún, however, does not mean that the issues of commercializing public goods and services, as well as cross-border investment "protection" treaties, are off the table.

2.4 Investment "protection" in international treaties

First of all, there are many different definitions of the term foreign investment: The U.S.A., e.g., pursues a broad definition of the term, which includes foreign direct investment, portfolio investment and short-term speculative investment vehicles, in the NAFTA as well as in the FTA with Chile. The EU favors a more narrow definition, which excludes portfolio and short-term investment, also in their FTAs with Chile and Mexico.

The investment rules of a (bi-)regional FTA, in contrast to those of a bilateral investment agreement, do not have any effects on third parties, i.e., any noncontracting parties. Even though the MFN principle also applies to regional FTAs, the accorded regulations do not have any validity for other international treaties, but are explicitly excluded from these – otherwise all regulations of EU treaties would automatically apply for all other states. In bilateral investment treaties that is not the case: If a BIT contains the MFN clause, then all BITs signed by this state automatically receive the same "best" (i.e., "best" for investors) conditions.

On a multilateral level there were already negotiations from 1996-98 within the framework of the OECD on a multilateral agreement on investment (MAI). Above all the U.S. and the EU had pushed these negotiations within the OECD, which, however, were declared a failure in December of 1998 (due mainly to the international pressure of various NGOs who were finally able to persuade France to simply say "non"). The investment regulations already stipulated in the NAFTA had served as a model for the MAI negotiations.

NAFTA is the first free trade agreement106 which awards an international juridical status to companies, corporations and investors: Chapter 11 of the NAFTA bindingly defines this investor-to-state dispute settling mechanism. [107]

The official guideline for states in their relationship with foreign investments is defined as following by the NAFTA article 1105:

"Each Party shall accord to investments of investors of another Party treatment in accordance with international law, including fair and equitable treatment and full protection and security."

The so-called investor-to-state dispute settlement mechanism gives companies as recognized juridical subjects the opportunity to take legal action on the basis of "discrimination" or "expropriation" against local, regional or national policies at an international court (ICSID108 or UNCITRAL) [109]. This juridical construct abolishes the principle of international law of giving priority to exhaust the national course of law: In the case of investor-to-state disputes the suitor, i.e., the company, decides whether to take national or international legal action – and the business-friendly NAFTA regulatory framework seems to be more promising for companies than the domestic legal course. This means the irreversible farewell from the Calvo-doctrin, which had been valid for almost 140 years particularly in Latin America, and according to which international interventions in order to enforce private claims could only take place after completely exhausting all national legal measures. [110]

According to NAFTA a "discrimination" against foreign investment can also occur by means of national legislation to protect environmental, health, employment or social rights [111], if an investor sees his enterprise restricted or disabled according to the criteria of National Treatment defined by article 1102 of NAFTA, or by the MFN clause defined in article 1103.