Christian Russau (Forschungs- und Dokumentationszentrum Chile/Lateinamerika e.V. - FDCL):

Enforcement of international trade regimes between the European Union (EU) and the Common Market of the South (MERCOSUR)? Foreign Direct Investment as the object of free trade negotiations: Between investors' rights, development and human rights

Translated by Jan Stehle, ed. FDCL-Verlag, Berlin, January 2004

Download [pdf 2.519 KB]

<<< back to chapter one & two [deutschsprachige Version]

Chapter 3:European foreign investment in Latin America and MERCOSUR: An opportunity for development and human rights?

3.1 European foreign investment in Latin America and geo-strategical trade competition

Among the 15 largest non-Latin American multinational corporations which operated in Latin America in 2001, there were 5 transnationals from the European Union – four of them were among the 5 largest: 1. Telefónica (Spain), 2. Coca Cola (USA), 3. VW (Germany), 4. Daimler-Chrysler (Germany), 5. Endesa (Spain).

"Considering re-investment and investment via third countries Germany ranks third in the list of Latin America’s investment partners with an investment stock of 42 billion US-dollars preceded by Spain and the USA [...] more than 85% of German investment in Latin America concentrates on the manufacturing industry [...] and the volume of production of German subsidiary companies in Latin America amounted to approximately 65.3 billion US-dollars and [exceeded] total German exports to the region (approx. 16 billion) by more than four times." [122]

According to numbers from the "Lateinamerika-Konferenz der deutschen Wirtschaft" (Latin American Conference of the German Economy) more than 10,000 German companies maintain economic relations with Latin America. Around 2,800 German companies have representations, branches or production sites in Latin America.[123] Mr. Rösler from the Ibero-Amerika-Verein, which is an institution close to the German employers’ umbrella organization BDI, concludes in his annual report:

"German direct investment in Latin America plays a more important role then can be deduced from the numbers on the stock of direct investment. Independent of the question how high German direct investment in Latin America really is, this region remains of strategical importance for the German economy. Apart from western Europe, Latin America is the only region in which German companies occupy key positions in certain industrial sectors, for example, in the automobile, chemical, pharmaceutical, electrotechnics and engineering sectors." [124]

This "imprecision" regarding the question "how high German direct investment in Latin America really is" can be explained, on the one hand, by the reinvestment of companies who have already established residency, which by definition cannot be registered by the criteria of foreign investment flows, and on the other hand, by investment flows via third countries [125], so that the real origin of capital is not recorded by the central bank`s statistics. German direct investment in Latin America, which is recorded by FDI-statistics, concentrates mainly on Argentina (which has 7.9% of the total amount of German foreign investment in Latin America), on Mexico with 21.5% and, with the highest percentage of investment, on Brazil with 26.4%. [126]

Since the second half of the nineties Spanish corporations have concentrated their foreign investment in Latin America on Argentina, Brazil and Chile, focussing for the most part on the take-overs of former state-owned companies in the services, telecommunication and banking sectors, but also on the industrial areas of energy and petroleum all over Latin America.[127] Spanish corporations – unlike the German ones, for example – have been the leaders in the participation in the wave of privatizations and liberalization in Latin America in the nineties.

Telefónica, for example, according to the 2002 ranking of the AméricaEconomía journal, is the largest foreign corporation operating in Latin America: Adding up all of the investments of Telefonica’s subsidiaries in different Latin American countries [128] amounts to total investments of more than 30 billion Euros [129] from which 31 percent of Telefónica’s global total revenue was obtained. [130] Telefónica’s focus lies on Brazil, where more than 17 billion US-dollars were invested over the last five years. [131]

Telefónica’s profits are to a large extent due to their business in Brazil, according to the corporation’s global numbers. And this is obviously not ultimately due to situations like the one which occurred in the state of São Paolo, where after the takeover of Telesp by Telefónica the fluctuation reserve against variations in power of 20% was abolished for reasons of costs, with the consequence of severe supply bottlenecks in the metropolitan São Paolo area, where Telesp, now a subsidiary of Telefónica, is the only network supplier. This situation even led to the appointment of a parliamentary fact-finding committee, Commissão Parlamentar de Inquérito (CPI).

According to the Ranking500 of AméricaEconomía, in 2002 the Telefónica –subsidiary, Telesp, realized sales of 2.855 billion US-dollars and net profits of 304.5 million US-dollars. [132] Telefónica is not only in the telecommunications business, its subsidiary Atento is Brazil’s largest provider of telemarketing services and among other things has taken over all call –center services for FIAT in Brazil. [133] According to the Estado de São Paulo, as of October 27, 2003, Atento plans to export this kind of call –center services to the world market. [134] They were sued in 1999 by the union of telemarketing employees, Sintratel [135] several times for paying wages lower than the collective agreement of only 83% of the sectoral compensation system [136] and for not complying with labor laws.

The Banco Santander Central Hispano (BSCH) is the third largest private bank in Brazil [137] with net profits in 2001 of one billion Reais [138] it is the largest Spanish bank and the second largest European bank with a market capitalization of 31.185 billion Euros (as of December 31, 2002). It has 104,000 employees on a global basis, of which 56% are employed outside of Spain. [139] In Brazil, contrary to previous accords with labor unions, one of the first actions of its subsidiary Santander Banespa was to cut jobs. [140] The BSCH and the Banco Bilbao Vizcaja Argentaria (BBVA) invested around 25 billion Euros and thereby at the end of the nineties were the largest and the third largest foreign bank in Latin America respectively [141], a position which the BSCH in the meantime has passed to Citigroup, which took over the Mexican BANAMEX for 12.5 billion US-dollars. In 1990 the market share of foreign banks in Argentina was only 10 percent, in Brazil six percent and in Mexico zero. In 2001 foreign banks accounted for 61 percent of the market in Argentina, 49 percent in Brazil and 90 percent in Mexico. [142]

The Spanish electricity provider Endesa has now accumulated 23 subsidiaries in Latin America. It is the largest producer and supplier of electricity in the region [143] and makes 40 percent of its turnover in Latin America. [144]

"ENDESA is one of the largest private electrical groups in the world, with a total installed capacity of 42,000 MW, 133,600 GWh distributed capacity and more than 20.5 million customers in 12 countries. ENDESA´s strategy is focused on the profitability, on the electricity business and on customer service." [145]

Endesa had profits of 11.995 billion Euros in the first nine months of 2003 and "earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) rose by 1.4% to 2.295 billion Euros." [146]

Endesa is Chile’s largest private corporation: The Chilean subsidiary of the Spanish parent enterprise Endesa, Enersis, had in 2002 annual sales of 3.45 billion US-dollars and has a subsidiary in Chile that acts under the name of the Spanish parent company, Endesa, which had a turnover of 1.3 million US-dollars in 2002. [147] Endesa has been a thorn in the side of environmentalists and the Mapuche population for years because of the six (in part planned and in part already completed) hydroelectric power stations in the Bío-Bío region. [148] The same is true for Endesa in the Brazilian federal state of Goiás, were in 2003 a parliamentary inquiry committee, CPI, concluded that the selling of the hydroelectric power station Cachoeira Dourada and the subsequent exclusive energy-supply contract between Endesa and the federal state was not only illegal and can be considered an adhesion contract, but that it has also created a damage of 715 million Reais for the federal state of Goiás. [149] In April a court [150] had suspended this contract, because it had set monthly costs of 17.5 million Reais for the energy to be supplied, even though the average price at this time was 7 million Reais for the same amount. [151]

Moveover, the Spanish Repsol had catapulted itself to the top [152] through the acquisition of the Argentinian oil company YPF for 15.2 billion US-dollars and currently has to confront a legal dispute with the Mapuche population who demand compensation for damages of 445 million US-dollars from YPF Repsol. [153] In Brazil the Luxemburgian steel-giant Arcelor, the world’s largest steel-producer, has positioned itself economically very well: Arcelor has far-reaching ambitions and sees "Brazil as a strategical objective":

"Brazil is seen as a key region for investment by many large steel-producers – in part due to the good long-term economic perspectives of the region, but also due to the low labor cost, through which many of the local steel plants are highly profitable." [154]

Arcelor holds 28 percent of the Companhia Siderúrgica de Tubarão (CST) through its preferred and common shares, whose market value amounts to one billion US-dollars, and 55 percent of the shares of another big steel-producer, Belgo Mineira, which in 2002 had sales of 896.4 million and net profits of ten percent, 89.8 million US-dollars [155]. Arcelor currently (2003) produces nine million tons of steel in Brazil annually and plans to raise this number to 12 million tons by 2006. "However, the plans to expand are in direct conflict with the goal of the Brazilian development bank BNDES to retain a large share of the sector in Brazilian hands by merging all important Brazilian steel-producers." [156] In 2003 Arcelor angered many environmentalists and the administration of the justice through the environmental damage caused by the leakage of chromate in the delicate Mata Atlântica-region.[157] Chromate consists of a so-called hexavalent chromium and is used in the heavy metal processing industry: Hexavalent chromium is considered carcinogenic by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), an organization of the World Health Organization (WHO): "Dry or wet chromic acid is corrosive to the eyes and skin tissue. Contact of very small quantities of dust or mist with the eyes can quickly result in severe burns. Skin contact can cause severe burns, external ulcers and ulcerations of broken skin." [158]

Transnational corporations, including European corporations, do not appear to consider their contributions to the "free economy" contributions to sustainable development in the respective countries or regions, as is often stated in a publicity-effective manner, to be a top priority of their engagements in the countries of Latin America. Also the issue of human rights in their indivisibility, which do not only contain the civic-political rights of the "Civil Defense Act", [159] but also economic, social and cultural human rights [160], do not seem to constitute a basic role model for the actions of European transnational corporations.

Europe’s economic interest in the Latin American countries is not uniform: In the course of the privatizations and liberalizations of the last few years Spanish corporations above all have tried to take over entire economic sectors by buying state owned companies all over Latin America. German corporations, for example, which traditionally have a relatively strong presence in Latin American domestic markets, have not participated in this wave of takeovers. Dutch corporations, on the other hand, who had participated in the takeovers in the nineties to a minor - but nonetheless significant – extent, are once again partially pulling out: The Dutch retail corporation Ahold, confronted with payment difficulties, is just one example of this.[161] Other European corporations have also backed out of Latin America: For example, the French Crédit Agricoles and the ScotiaBank, which as a result of the Argentine crises pulled out of Argentina. This retreat can nonetheless be seen in the global decrease of foreign investment flows. [162]

International capital flows in terms of FDI can be explained to a large extent by cash flows in the area of M&A. [163] Throughout Latin America the market for M&A in the first half of 2003 has shown clear signs that Latin American companies have been increasingly positioning themselves (Latin American M&As accounted for 62.5 % of the total at the end of June 2003, according to estimates from Thomson Financial). This is, however, most likely due to the drawback of European and North American companies. At the same time it has to be mentioned that reinvestment using acquired cash-flows made by foreign companies who already reside in Latin America is statistically not treated as foreign capital, just as the country specific classification of FDI-flows, which pass through so-called tax havens, is not possible:

"It is striking that, according to the estimates of central banks and ministries from Latin America, one fifth of FDI comes from other countries, i.e., primarily from tax havens. But tax havens seem to merely be of transitional nature for investment by companies from the industrial countries, yet statistics of the industrial countries give similar numbers for the direct investment of their companies in the Caribbean tax havens." [164]

The positioning of European corporations in the Latin American domestic markets by means of direct investment also has to be seen in the context of geostrategical economic competition with the U.S.A. And this competition in the course of 2003 has significantly approached the barrier of tariff –wars, which is not only being led in a disguised way anymore: The falling value of the US-dollar combined with the simultaneous rise of the Euro deteriorates the foreign trade position of Europe insofar as European exports become more expensive and US-American exports become cheaper. As the Euro continued to rise throughout 2003, four crucial events occurred in terms of foreign trade:

• First of all the WTO, within the framework of the long-lasting dispute between the EU and the U.S.A. on the U.S. practice to indirectly subsidize the exports of US-companies by means of so-called "Foreign Sales Companies" (FSC), granted the EU the right to place trade related sanctions like import tariffs on US-American commodities for up to four billion US-dollars, which constitutes the highest ever trade –sanction. [165] The products affected by this measure do not have to be equivalent products. The EU, in the framework of cross-retaliation, can also place tariffs on other products. [166] The EU initially did not make use of the sanctions, allegedly not wanting to damage the multilateral negotiation process within the WTO, until

• Secondly, the fifth ministerial conference of the WTO in Cancún, México, "failed" in September of 2003 and

• Thirdly the WTO Dispute Settlement Body on November 10, 2003 [167] also declared US-import tariffs for foreign steel as illicit and again allowed the EU to cross-retaliate up to an amount of 2.242 billion US-dollars [168] and

• Fourthly the EU on September 22nd – shortly after the "failure" of Cancún – reactivated the three year old WTO-dispute with the U.S.A. referred to the so-called 1916 US Anti-Dumping Act, in order to also take "punitive or protectory measures" in this case.[169]

After the "failure" of Cancún and after it became clear that the multilateral negotiations of the WTO could not be brought to an end within the schedule of the Doha Agenda, the U.S. as well as the EU were increasingly able relax the lip services concerning a "real multilateralism", so that an intense activity of bilateral negotiations on FTAs could start with selected countries of interest for the U.S. [170] and the EU [171].

It is neither a thematic nor a timely coincidence, but a reflection of the competition between the U.S.A. and Europe in trade-related questions, that the EU, after the "failure" of Cancún as well as the weakening of Europe in foreign trade due to the weaker dollar and the strengthening Euro, is planning to activate the retaliatory measures assigned by the WTO in the case of the "Foreign Sales Companies" as well as the "US 1916 Anti-Dumping Act" dispute case, also in order to simply put a stop to an impending rise in imports from the US caused by a falling dollar. Even though the implementation of the WTO judgment is doubtful, as the "material damage" caused is not directly restituted to the claimant and its realization depends on the trade related countermeasures, the political dimension of this procedure should not be underestimated.

The increasingly openly led trade competition between the U.S. and the EU has thereby significantly approached the boarderline of an open trade war.[172] Literally at the last minute president Bush (jr.) lifted the tariffs in the "Steel Safeguard Case", in order to avoid cross retaliation by the EU and other countries. – This cannot obscure the fact that this economic conflict is latent and consequently the currency-competition between the Euro and the dollar is also affected. The competition for markets between the EU and the U.S. is also revealed in Latin America: The European bilateral strategy after the implementation of the FTAs with Chile and Mexico, to rapidly conclude a bilateral agreement with MERCOSUR – if possible before the signing of the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA/ALCA) – is also a reflection of this:

"The race [between the U.S. and Europe] will not be continued in Latin America alone, but it is the playing field where, with the FTAA and the EU-MERCOSUR projects, the competition between the Euro and the dollar is reflected most explicitly." [173]

According to a report from the ila journal, the feeling of rivalry between the U.S. and Europe concerning the competition for Latin American markets has in the meantime reached a critical mass:

"German economic officials look towards a possible overall American free trade area with discomfort." [174]

And the new fourth generation of regional trade agreements aims primarily at enforcing European commercial and economic interests:

"The EU has so far not been able to demonstrate in a convincing manner, that the extensive agenda of the new generation of trade agreements promotes a broad socially just and ecologically compatible development in the South. The European trade policy is a horse of a different color: The Community aims to expand its exports to the countries of the South and will concentrate on safeguarding new markets, particularly in the areas of high technologies and services, but also with respect to the enlargement of foreign investment-flows in the processing sector, privatization-programs and investment in extractive industries. Strategically the EU is out to set a trade-related counterbalance to the U.S. trade power by rapidly continuing the negotiations with MERCOSUR and the African ACP-countries while the U.S. is also targeting the same markets with their new Pan-American free trade area (FTAA) and the "African Growth and Opportunity Act" (cp. W&E 1/2003). A differentiated treatment, which promotes development in the weaker southern countries, seems to be of minor importance here. Even though some of the new agreements reveal some asymmetrical elements with respect to the timetable and extent of liberalization during the transition period, in the end the economically more powerful negotiation block will obtain the larger economic benefit." [175]

3.2 European foreign investment in MERCOSUR

The European economic interest in the Common Market of the South (MERCOSUR) lies in the realized and expected profits obtained by the resident European corporations within the domestic markets and in the area of foreign trade. In terms of foreign trade the EU between 1990 and 1994 was able to "more than double" their exports to MERCOSUR countries, whereas imports rose only slightly: "a consequence of the unilateral liberalization on the part of the MERCOSUR countries. Especially Brazil, which lowered their tariffs from an average of 52 to 14 percent, became a desired market." [176]

Between 1995 and 2002 the EU realized a current account surplus of 4.2 billion US-dollars with Brazil. According to the German employers’ umbrella organization BDI:

"[...]since 1995, in its trade with Brazil, Germany has been benefiting from surpluses averaging approximately 1.5 billion dollars a year." [177]

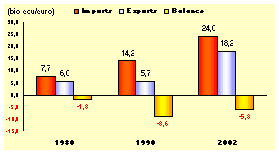

The European Union as an economic block is the main foreign-trade partner of MERCOSUR. The trade balance creates the following picture:

EU-Merchandise Trade with MERCOSUR

Source: DG Trade: trade-info.cec.eu.int/doclib/html/111832.htm

The largest trade balance deficits on the part of MERCOSUR are realized in the services sector; the EU shows the respective surplus:

EU Trade in Services with MERCOSUR

Source: DG Trade: trade-info.cec.eu.int/doclib/html/111832.htm

European foreign trade with MERCOSUR is apparently still a good business for European corporations, even if profits, as a result of crisis situations in MERCOSUR, e.g., in Argentina in 2001/2 due to the rapid devaluation of the Peso, are not always as high as expected.

The U.S.A. lags behind the EU in MERCOSUR, both in the area of foreign trade, as well as with respect to FDI. Even if in absolute numbers the U.S. is still the largest direct investing country, the combined numbers of the EU countries’ investment account for the largest share of FDI in MERCOSUR amounting to 60% of foreign capital inflows.

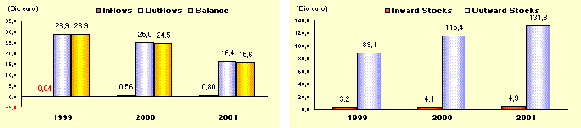

European FDI-Flows (the sum of the capital invested over one year) to MERCOSUR amounted to 28.9 billion Euros in 1999, 25 billion Euros in 2000 and 16.4 billion Euros in 2001. The European FDI-Stock (sum of all realized investments) in MERCOSUR increased from 89.1 billion Euros in 1999 to 115.4 billion Euros in 2000, finally reaching 131.8 Euros in 2001:

EU Foreign Direct Investment with MERCOSUR

Source: DG Trade: trade-info.cec.eu.int/doclib/html/111832.htm

"Brazil and Argentina have since long been a focal point of FDI outside the OECD area by European companies. [...] Traditional FDI patterns were the result of European investors’ preference for large and protected markets. Notably in the automobile and chemical industries, the size and growth of markets provided the major stimulus to FDI in the MERCOSUR region. Multinational companies used FDI mainly to overcome import barriers." [179]

While in 1991 only three European corporations where among the top ten Argentine companies, in 1999 there where already seven: YPF Repsol, Telefónica, Telecom, Supermercados Norte, Shell, Supermercados Discos and Carrefour. [180] Particularly in the business sectors, which were privatized and primarily sold to foreign corporations, like telecommunications, aviation, water and wastewater market, energy and gas, the highest percentual layoffs were implemented through firings and outsourcing in Argentina as a result of the privatizations. In terms of employee numbers, setting the index of 1990=100 shows that in 1998 the index in the telecommunications sector fell to 51, in aviation to 44, in the water and waste water sector to 52, in gas to 48 and in the energetic sector to 30. [181] According to these numbers no new jobs were created through FDI in Argentina in the nineties, instead jobs were cut.

The liberalized drinking water market had turned out to be an especially sensitive area in the nineties. Between 1991 and 1999 one third of the Argentinian potable water market, which covers the water supply of nearly 60 percent of the population, was privatized. [182] The biggest takeover was the acquisition of Obras Sanitarias de la Nación (OSN) by Aguas Argentinas, of which the French Suez-Lyonnaise des Eaux holds 39.93 percent, Aguas de Barcelona holds 25.01 percent (of which Suez is the majority shareholder, next to the Spanish Endesa with 11.64%) [183], the French Vivendi holds 7.55 percent and the British Anglian Water [184] holds 4.25 percent of the shares. [185] In 1993 Aguas Argentinas had agreed to invest 4 billion US-dollars to improve the infrastructure and expand the water pipe and sewerage systems. In exchange the Argentinian government accepted that the company’s personnel would be cut by 47% (from 7,600 to 4,000). [186]

Initially, Aguas Argentinas lowered the rates by 26.9%, but by 2001 the rates had increased by more than 100 percent. According to its board of directors between 1993 and 2001 the company had invested 1.7 billion US-dollars and had achieved an average profit rate of 23 percent during the 1990s as compared to 7-8 percent in the water industry in the United States and the United Kingdom. [187] While the company claims to have connected nearly 2 million people to the water system and 1.15 million to the sewer network between 1993 and 2001, the provincial government argues that 3.5 million people within Aguas Argentinas’ potential clients still lack water and sewage services. [188] In light of the financial crisis in Argentina, in 2002 the government abolished the "convertibility" systems that had pegged the Peso, i.e., the company’s profits could no longer be converted to the Dollar at an even parity. This led Aguas Argentinas and its Argentine subsidiaries to file complaints together with their European mother firms at the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), on the basis of the bilateral investment agreement between France and Argentina, which was signed on July 3, 1991 and came into force March 3, 1993. In addition, Argentina, at the same time as Chile and Bolivia, already ratified the ICSID-Convention, which constitutes another juridical basis for foreign investors. But as a complaint at an ad-hoc-arbitration court takes some time, Suez saw itself obligated to write-off 500 million US-dollars in its 2002 consolidated balance sheet. [189]

The French Vivendi sued the Republic of Argentina alleging "violations of the BIT’s provisions on fair & equitable treatment and against expropriation without compensation" [190] in the case of its subsidiary Compañia de Aguas del Aconquija S.A. from the Tucuman region (ICSID Case N° ARB/97/3). [191] The Enron subsidiary Azurix also filed a complaint against the Republic of Argentina with the ICSID on October 23, 2001 (ICSID Case N° ARB/01/12) concerning its water concession contract.

This wave of dispute cases initiated by private investors against the Republic of Argentina is not restricted to the water sector only, but also extends itself to the gas and energy sectors, where, e.g., the Belgian-French corporation Total Fina Elf has demanded a compensation of one billion US-dollars, filing with the ICSID, due to the freezing of "hydrocarbons prices and derivates, plus the devaluation of the Argentine currency" in the course of the Argentine crisis in 2002. [192] The Electricité de France, EDF, has issued a similar complaint against the Republic of Argentina [193] and also the German company Siemens is demanding compensation payments: The news agency NfA, Nachrichten für Aussenhandel, reported that:

"Siemens wants 500 million US-dollars from Argentina

Berlin (vwd) – The Siemens AG, Munich, has demanded 500 million US-dollars in compensation payments from Argentina for the cancellation of a contract. As emanated from a note directed to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) on Monday, the company has filed for an arbitration proceeding at the International Center of Investment Disputes of the World Bank. Siemens argues that, through the cancellation, Argentina has infringed an investment treaty with Germany." [194]

Complaints of private companies against states at the ICSID on the basis of bilateral investment treaties have risen from five in 2000, to twelve in 2001, to fifteen in 2002. [195] What is explosive about these allegations, which are based on BITs, is first of all that such allegations can only be undertaken by foreign private investors and that domestic investors are not allowed to take such legal actions, and second of all that there is a procedural detail that every complaint filed on the basis of BITs is held before an international arbitration courts, with special emphasis on business and investors’ rights and not on social or environmental aspects. Luke Eric Peterson of the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) comments, regarding the wave of individual complaints against the Argentinian government:

"A troubling feature of this growing spate of cases against the Argentine Republic, is that foreign investors are mounting a series of individual ad-hoc arbitrations which may challenge essentially the same government measures. Because these arbitrations are proceeding in parallel, and Tribunals are not strictly bound by the determinations of other (or earlier) Tribunals, the stage is set for a series of potentially divergent or even conflicting rulings." [196]

It is not surprising that, given these experiences of the Republic of Argentina, the population of the neighboring country of Uruguay is already sensitized to the problem of privatizations. Already on December 12, 1992 the Uruguayan population had voted in a referendum against a privatization of electricity, telecommunication and petroleum. Also moved by the Argentinian experience the Uruguayans collected 280,000 signatures against the privatization of water in 2003 in order to hold a referendum in November 2004, which would permit a constitutional change and define the utilization and protection of water resources as a fundamental right which has to be administered exclusively by the public authorities. [197]

A large part of the extensive Guaraní water reservoir ("Acuífero Guaraní") is located in Uruguayan territory. Likewise a majority of Uruguayans on December 7, 2003 voted against "law 17,448" which would have permitted the privatization of the national petroleum company Ancap. [198] Because as long as state enterprises are not privatized, there is no danger of becoming the object of claims of private investors, which are written down in the existing international investment treaties. Uruguay has signed 15 bilateral investment treaties so far, of which seven have entered into force. [199]

Brazil in this context (still) has a special status, as the Brazilian congress has not ratified one single investment treaty (yet). Nonetheless, for decades Brazil has been leading the list of FDI recipient (emerging) countries. Taking a look at FDI in Brazil over the last 30 years (from 1969 to 2000) from the perspective of competition between European and US-American transnational corporations [200] the FDI of European corporations do not fall short of the U.S. companies: In 1969 there were fourteen U.S. and twenty European transnational corporations among the Brazilian Top-100 list of major companies. Four of the European companies were German, three British and three French. [201] In 2000 there were already five companies each from Germany, France and Italy and three from Spain among the Top-100, totaling 29 European transnationals versus 19 from the U.S.A. Telefónica together with Telefónica Celular alone had sales of 6 billion US-dollars followed by Volkswagen do Brazil with sales of 5.73 billion US-dollars. [202]

European automobile producers in MERCOSUR, like Volkswagen do Brazil, traditionally produce, to a large extent, for the domestic market. As a result of the weak Brazilian economy in 2002 and 2003 and given the importance of the Brazilian production and sales for the consolidated accounts of the Volkswagen AG globally, the Brazilian subsidiary Volkswagen do Brazil has been responsible for a major share of Volkswagen’s overall losses in 2002-2003. [203] VW do Brazil has an annual production capacity of 740,000 vehicles, but currently [2003], due to the "weakness in demand", only 473,000 vehicles are being produced. [204]

In times of such "weaknesses in demand" transnational corporations like Volkswagen, which like to praise their "social responsibility" towards their employees in a publicity-effective manner, don’t take labor law too seriously, as the 2003 corporate strategy to confront these losses shows: Cost-management through layoffs. And in doing so the Wolfsburg headquarters has not been squeamish and with only shareholder value in mind is ready to pass over labor laws as well as over their own otherwise publicly effective, marketed, both internally as well as globally valid codes of conduct.

Volkswagen planned to reduce personnel in the plants in the federal states of São Paulo, Tabaute and Anchieta by 4000 employees. Anchieta is the oldest Volkswagen plant in Brazil and at the same time the largest Volkswagen entity abroad. In order to reach this goal, without violating the job security agreement between the union and the corporation which is valid until 2006, the 4000 employees are to be transferred to a Volkswagen employment and training firm –in response the VW-employees were up in arms and announced strikes. Volkswagen CEO Bernd Pischetsrieder felt he was in the position to pass over all valid Brazilian labor legislation, and to threaten all strikers with layoffs, [205] a statement which was explicitly confirmed by the Volkswagen spokesman. [206] This in turn induced the Brazilian Labor courts [207] to consider taking legal action against the VW-board of directors. [208]

Whether the right to strike is a fundamental right, however, is being disputed. The right to strike is not explicitly mentioned in the ILO Conventions No. 87 "on freedom of association and the protection of the right to organize" of 1948 and No. 98 "concerning the application of the principles of the right to organize and to bargain collectively." But the ILO Committee on Freedom of Association (CFA) considers the right to strike to be an inseparable part of the principle of freedom of association. According to employers’ associations and some governments the exclusion from the ILO Conventions permits the opposite conclusion. [209]

The "Global Compact" initiated by UN Secretary General Kofi Annan at the beginning of 1999 defines, in the third of its nine principles, the freedom of association and the right to collectively bargain.[210] The right to strike again finds no explicit mentioning here, instead the formulation leaves room for interpretation:

"These freedoms also allow for industrial action to be taken by workers (and organizations) in defense of their economic and social interests." [211]

Volkswagen has not only signed this Global Compact of corporate responsibility, and thereby recognizes the right of "industrial action to be taken by workers (and organizations) in defense of their economic and social interests," [212] but also had effective publicity on June 6th of 2002 in Bratislava, by declaring that Volkswagen was the first automobile corporation to lay down a code of conduct on social rights and industrial relations. According to IG-Metall (German Metal Workers Union) president, Klaus Zwickel, Volkswagen with this social charta is "rendering pioneer’s work" and giving the right answer to globalization." [213] In this intra-company "Declaration on the social rights and the industrial relations within Volkswagen" [214] the following is said in § 1 Basic Objectives, on the freedom of association in 1.1:

"The fundamental right of all workers to form unions and workers' representations and to become a member of them is recognized. Volkswagen and the unions or workers' representations work openly together in the spirit of a constructive and cooperative management of conflicts" [215]

But not only international law or internal company codes of conduct oblige VW to respect fundamental labor norms. In addition Brazilian law, according to article 9 of the Brazilian Constitution, there is the obligation not to hinder the right to strike. [216] The pressure of Unions and Brazilian Labor courts, which insisted on abidance by the law, finally led to an agreement between the union and the corporation, which was supported by 75 percent of the 13,000 employees from the plant in question, to cut 1,923 jobs in exchange for severance payments. [217] – This unfavorable interlude, with respect to shareholder value (see the consolidated balance sheet), will surely play an important role, in terms of the global bargaining power for investment locations and advantages and disadvantages of locations in the next corporate decisions of the Wolfsburg board of directors: in other countries abroad this "disadvantage of location" concerning labor laws and the degree of union organization would not exist.

German companies were only marginally involved in the privatizations of former state enterprises in Brazil during the nineties. Other European corporations, led by Spanish companies, were large-scale participants of this wave of privatizations, which occurred as a result of the IMF conditions placed on Brazil, one of their major debtors. The share of foreign capital among the Top-500 Brazilian firms rose from 31 percent in 1991 to 45.8 percent in 2001. [218] At the same time as a consequence of privatizations of state enterprises the state’s participation in the top-500 Brazilian companies fell from 26.6 to 19.7 percent.

The countries of origin of the FDI inflows in the case of privatizations were the U.S.A. (16,5%), Spain (14,9%), Portugal (5,7%) and Italy (3,1%). [219] From the perspective of the countries of origin, Portugal maintains the top position with respect to the relative importance of its investment in Brazil: Portugal’s FDI flows to Brazil amounted to 15 billion US-dollars over the last 5 years, accounting for approximately 60% of Portuguese FDI –outflows, [220] a circumstance which might refer to the strong mutual dependency between Brazil and Portugal.

The European FDI stock in Brazil amounted to 76.8 billion Euros in 2001. [221] Before the big wave of privatization in the middle of the nineties the capital and production intense automobile sector was leading in foreign investment, until the neoliberal privatization, especially of the telecommunication and banking sectors, had produced a move from production intensive sectors to the services sector. In Brazil from 1991 to 2002 "only 0.1% of revenues from privatization (which totaled 42 billion US-dollars) came from German firms." [222]

This rise in FDI in Brazil, however, has not produced any impact on development, but to the contrary: According to a Unicamp study in 1997, around 95 percent of FDI occurred in the area of M&A and thereby had no impact on job creation [223] and only five percent was categorized as Greenfield Investment. [224]

In general terms the strategic orientation of FDI in Brazil– focussed on the internal markets of Brazil or MERCOSUR, and thereby not on exports to the world market - had not changed until the end of the nineties. [225]

At first glance one might get the impression, that through the relatively high FDI inflows from 1998 to 2000 into the privatized service sector, like telecommunications and banking, nothing has changed with this scenario of orientation towards the internal market. But for an economy like the Brazilian one it is macroeconomically essential to get FDI into the country with the hope that this might stimulate the internal market. But the economy is forced by market logic to use these FDI –flows, above all, in order to attract additional foreign currency – and this is mainly through exports. This picture might change, but the exact course is currently hard to predict. A trend in this direction, however, is very likely to occur as not only the foreign corporations which operate in MERCOSUR are interested in profits and comparative cost advantages – which is often labeled with the nice term "efficiency seeking", but also the four MERCOSUR governments are very keen to obtain export surpluses in order to avoid strong disequilibria in the balance of payments and to avoid new financial crises.

And in this sense both governments and corporations – in this case hand in hand – would welcome a free trade agreement – the only question seems to be the details of this agreement. The different interests of the participants on both sides of the Atlantic related to the rapid conclusion of an "Interregional Association Agreement," which in the beginning had an "ambitious" [226] negotiating agenda to liberalize market access on the part of both sides to agricultural markets, the services and investment sectors and cross-regional binding rules for public procurement, can be depicted alongside the thematic complex of "investment."

Chapter 4:The free trade agreement between EU and MERCOSUR: The case of Brazil

4. 1 The free trade agreement between EU and MERCOSUR: Interests of companies, lobby groups and governments – The case of Brazil

European corporations, which have been operating in MERCOSUR for years and which mainly concentrate on the domestic markets within MERCOSUR, in one respect have a smaller interest in rules for tariff reduction within the framework of a future FTA, as compared to, e.g., companies which produce in Europe and hope for sales advantages in foreign trade. European automobile producers in MERCOSUR, such as Volkswagen do Brazil, traditionally produce primarily for the domestic market. Nonetheless, Volkswagen do Brazil is at the moment apparently trying to diversify its strategy of focussing on domestic markets through exports of automobiles produced in Brazil to the United States, Asia, Europe and Africa. [227] This new policy would also benefit from a tariff reduction in these markets through a FTA: the European import tariffs for automobiles produced abroad are at 10 percent, in accordance with the WTO, for cars produced in Brazil according to the GSP tariffs (Generalized System of Preferences) [228] they are currently at 6.5 percent. [229] In MERCOSUR, however, import tariffs on automobiles produced outside of MERCOSUR are currently at 35 percent. Such a constellation comes in handy for corporations already located in MERCOSUR, but for corporations that are not yet present in the Common Market of the South, this at the same time means a "disadvantage of non-location."

Mercedes Benz do Brazil in 1997 still produced forty thousand trucks and buses. In 2002 this number had fallen to 5,451 units. In 2003 production numbers again rose to 38,000, of which 9,300 were exported, which was in particular due to the increasing demand in Argentina. For 2004 a production of around 40,000 trucks and buses is expected, where 30,000 will be produced for the Brazilian domestic market – which means that Brazil will advance to be the second largest market for Mercedes trucks and buses, led by the U.S. with 90,000 units and followed by Germany with 27,300. On the other hand, the production of automobiles in the principle Mercedes plant in Brazil, Juiz de Fora, has been losing money for years, which according to management is due to the devalution of the Brazilian Real: again Mercedes here is primarily producing for the Brazilian domestic market. [230]

Transnational corporations in MERCOSUR, which are oriented towards domestic markets, are not pursuing any standardized interests with respect to the settlement of a free trade agreement between the EU and MERCOSUR. On the one hand, the opening of markets through tariff reductions within the framework of an FTA would mean for these companies additional competition from corporations, which are currently not residing in MERCOSUR. [231] On the other hand, exports to countries outside of MERCOSUR could increase through FTA and national regulations like, e.g., the minimum quota on the number of local employees, could be lifted through an international treaty.

This situation might shed the first clear light on the, to some extent, differentiated positions of interest of the different players with respect to the ongoing free trade negotiations between MERCOSUR and the European Union: First of all, for foreign companies already present in MERCOSUR it is an advantage to have a better position on the markets than the non-resident companies would have, and second of all, it is an even bigger economic advantage if, by means of an association treaty between the EU and MERCOSUR, the regulations on capital transfers and minimum quotas for local suppliers or local employees should be offset.

"lose any possibilities in the area of trade. We are not willing to accept a formulation [in the ALCA negotiations], which, from our perspective, would impose self-restraints with respect to market access. Trade and investment are central issues for us." [233]

On the other hand, the Uruguayan negotiators were at first reserved with respect to the issues of public procurement in all negotiating agendas. Public procurement does not form any part of the most recent bilateral investment treaty between Uruguay and Mexico, but at least the agreement was made to negotiate on the issues within two years after the conclusion of the treaty. With respect to the issue of investment the four MERCOSUR negotiation partners could at least agree on the preliminary desire, to give the negotiation of investment issues in the services area priority within the WTO. [234]

But it is one of the primary interests of the current MERCOSUR governments to maintain and use a certain amount of space for possible national or regional designs, a topic which is of special interest for the Brazilian government, which in its electoral program of 2002 explicitly mentioned the necessity of a national scope for design and decision with respect to national and regional development. The Brazilian president Lula in his speech at the fiftieth anniversary of the Brazilian Oil company Petrobras on October 3, 2003 emphasized the importance of such national performance requirements for the issues of jobs, technology and overall development. [235]

The Brazilian delegation for the WTO negotiations had traveled to Cancún – in accordance with its MERCOSUR partners – without an explicit position on the issues of investment and public procurement. But in the post-Cancún negotiation process the Brazilian delegation took the following position: With respect to the investment issue the Brazilian Lula-government, e.g., within the framework of the ALCA negotiations, vehemently argues, just as it did at the EU-MERCOSUR ministerial conference on November 12 in Brussels, that if there should be negotiations on the investment topic, these should occur on the multilateral level of the WTO.

Since Cancún Brazil has been positioning itself within the Alliance of the G-20, G-22, G-X [236], and has relatively strong negotiation partners on its side and insists on the universal guarantee of national scopes of design, development-focussed industrial and fiscal policies, the maintenance of local-content reglamentation and performance requirements.[237] The Brazilian negotiation delegation had already urged at the tenth round of the EU-MERCOSUR bi-regional negotiation committee (X. BNC) from June 23-27, 2003, that first a preliminary revision of the negotiation texts should occur and methods, negotiation modalities and general and specific definitions related to the investment issue should be treated, before the topic itself could be negotiated. [238]

Regarding the investment issue the Brazilian government has agreed – in accordance with its offer to the EU – to only admit post-establishment investment guarantees, i.e., guarantees for investment which have already been realized in the country, as opposed to the so-called pre-establishment guarantees according to which foreign investors, who feel discriminated against, e.g., by changes in legislation (environmental requirements, performance requirements, local-content rules, etc.)– without having materialized an investment in the country yet - can take legal action at international courts against this "indirect" expropriation. [239] The Lula-government explicitly opposes this possibility for so-called investor-to-state disputes in all its free trade negotiations. [240] In the same way the Brazilian government advocates exceptions in the area of liberalizing capital and profit-transfers, in order to, e.g., protect national economies against abrupt capital flight or speculative attacks in times of crises. [241] However, it does not go as far, as to mention the term "regulations on capital flows" explicitly.

The Brazilian government agrees with the European side that the investment definition only affects FDI and not portfolio investment. On the other hand Brazil is blocking one of the favorite issues of EU trade commissioner Pascal Lamy: public procurement. This highly sensible issue, which aims at the obligation to publicly tender, on an international level, every public expenditure which exceeds a certain amount, without retaining the possibility to impose any criteria other than the price. In this sense, e.g., the acquisition of toilet paper for public schools of a federal state (which supposedly exceeds the annual amount of 50,000 US-dollars), would have to be tendered internationally and would have to be awarded in a transparent manner to the best, i.e., the least expensive supplier. [242] With this the global market competition is reaching out to the last untouched areas. It is not hard to understand why MERCOSUR’s negotiation side is reluctant with regards to this issue of "transparency in government procurement", as contrary to the EU Commission.

With respect to the services sector, which in one of its four forms is tangent to the area of investment (foreign subsidiaries), the Brazilian side favors so-called positive lists. This means that all services –areas, which fall under the GATS regulation of the WTO or under the sectors to be liberalized under ALCA or EU-MERCOSUR, have to be mentioned explicitly in a "positive list". In this way they are irreversibly subjected to the rules of market access, national treatment, MFN clause and trade facilitation. All other service areas not on the list, or future service areas, would be explicitly excluded from the opening of markets in this context, unless one of the contract partners decided to unilaterally open up one of these sectors.

Still, these positive lists run the risk of being undermined by political pressures from the countries of the "North", so that more and more sectors might be subjected to "liberalization" and market opening, with all its potential social consequences. Fátima Mello, representative of the Brazilian NGO Fase and member of Rebrib (Rede Brasileira pela Integração dos Povos) has pointed this out emphatically. [243]

But the more eminent danger is that of a negative list: on the one hand, it is unclear what will happen to future services areas (what would have happened to the e-commerce sector, e.g., if there would have been a ratified negative list before the existence of this service sector?). Will they automatically form part of the areas to be liberalized or not? On the other hand, the danger exists that a negative list explicitly states, that the excluded areas constitute some kind of "exception" or a "deviation" from the rule, which later on, through international pressure of the big nations, e.g., can be abolished arguing a "normalization" of this rule.

On the European side the position towards the planned "Interregional Association Agreement" is naturally not unitarian. The German industrial employers umbrella organization, BDI, for example, considers the European agricultural subsidies as unbearable. The BDI vehemently advocates a FTA in terms of the German exporters: In this sense the BDI feels that the objective of international negotiations on services should be to open up markets. [244] All "market distorting" national decrees for investors, which are enacted in terms of the promotion of regional development, e.g., considering local suppliers, are a thorn in their side:

"The German industry has in the past always rejected attempts to pursue economic and industrial goals in a dirigistic manner with the help of trade-policy instruments and will continue to do so." [245]

The BDI uses its historically close relationship to the German government to represent the interest of its members, who operate in MERCOSUR countries, "commenting and complementing each offer coming from MERCOSUR or the EU" [246] and exerting influence by loudly propagating their ideas with respect to free trade and investment "protection."

The same position is argued by the Hamburg based Ibero-Amerika Verein, [247] which also speaks out against the European agricultural subsidies, [248] as well as the "trade and investment barriers" imposed by MERCOSUR.

The Ibero-Amerika Verein, together with the BDI, founded in 1994 the Lateinamerika-Initiative der deutschen Wirtschaft (LAI-Latin America Initiative of the German Enterprises) in cooperation with the Deutschen Industrie- und Handelskammertag (DIHK employers’ umbrella organization), [249] which advocates a broad FTA between the EU and MERCOSUR. In this sense the "Declaration of Frankfurt" of the Lateinamerika-Konferenz der Deutschen Wirtschaft from May 14-15, 2003 demanded the following:

"The Latin American countries will be explicitly encouraged in their efforts to promote structural reforms, privatizations, deregulation, liberalization and democratization. The creation and consolidation of a reliable juridical framework is of particular importance. [...}

The German enterprises once again call on the EU-Commission to speed up the negotiations of the planned agreement with MERCOSUR. In order to succeed in the negotiations, a more flexible position is needed in the area of EU agricultural policy." [250]

On the side of European governments Spain is the first-ranking advocate of the planned agreement, and the treatment of foreign investment is the central issue here:

"None of the EU countries with substantial investment in MERCOSUR want to cede terrain. Among those, e.g., in Argentina, Spain comes in first place (39%) followed by the U.S. (28%), France (7%), Canada (6%) and Italy (5%). Around the turn of the year [2001/2002, the author] the Spanish government besieged the Casa Rosada (seat of government) in Buenos Aires, in order to be able to transfer profits from Spanish companies in Argentina to Spain in foreign currency and not in devaluated Pesos. In July 2002 the Spanish members of the European People’s Party (EEP with parliamentarians from the German CDU/CSU and the Austrian ÖVP, among others) succeeded in persuading the European Parliament to adopt a statement regarding Argentina, that demands help, refers to the cultural roots and to a particular human right in modern societies, the right to property." [251]

An addition: in Brazil Spanish corporations dispose of a FDI stock of currently 25 billion US-dollars, which represents a share of 14% of total foreign direct investment in Brazil. [252]

The German government on its part has always pleaded for the interests of the German trade associations and, in the case of German interests in Brazil, can look back on a tradition of more than forty years. [253] From October 27-28 in Goiánia, federal state of Goiás, the 21st German-Brazilian Economic Meeting took place, organized by the BDI and its Brazilian partner organization CNI. [254] There it was regretfully stated that:

"German participation in the total Foreign Direct Investment in Brazil has fallen from more than 25% to less than 7%." [255]

In order to confront this decrease in the FDI flows between Germany and Brazil, the communities from politics and trade gathered in Goiánia proposed the following:

"The German side suggested that a bilateral investment protection and promotion treaty would further improve the conditions for foreign investment, especially for small and medium-sized companies, and asked for rapid ratification of the negotiated bilateral investment protection and promotion treaty. The Brazilian side stated that the issue is under review. It was agreed that the subject will return to the agenda of the next meeting. [...] The German side recognized the positive effect for further investment in Brazil potentially resulting from the adoption of the draft legislation on transfer pricing currently debated in Congress and encouraged the Brazilian side to join in the efforts for that purpose. [...] The German party reaffirmed its strong interest in the opening up of the reinsurance market. Brazil welcomed this interest and emphasized its commitment to the modernization of the sector. The German side raised concerns with high taxation of the insurance market and double taxation (in particular, COFINS and PIS on provisions). The Brazilian side recalled that its tax system is essentially the same for national and foreign companies and does not intend to discriminate Germany, neither in a positive nor a negative way. At the same time, reminded that the current double taxation bilateral agreement is favorable to the large majority of German and Brazilian business circles. [...] Both sides referred to the Third Meeting of Heads of State and Government of the European Union and of Mercosul, to be held in May 2004 in Mexico in the margins of the EU-Latin America Summit, and praised the decision to give a new impetus to economic/trade negotiations and to call a meeting between negotiators at the ministerial level in Brussels on November 12. As the biggest economies within their respective integration areas, Brazil and Germany renewed their commitment to progress in the EU-Mercosul negotiations and expressed their hope that the next meeting would help to further advance the process. Both sides agreed that the conclusion of an association agreement will be determinant in stimulating trade and investment flows." [256]

Economic relations between Germany and Brazil are not limited to the trade sector, German direct investment in Brazil has also reached a historically high level: São Paulo is the worldwide largest location of German industry, only being surpassed by the German Ruhrgebiet region (which is not a single city). Currently 1,200 German companies operate in Brazil and employ more than 250,000 people, mainly in the industrial sector:

"Concentration on the industrial sector: According to numbers provided by the Central Bank of the country in 1995 in Brazil there were the following distributions: automobile production & manufacture of components 32%, machinery and equipment 12%, chemicals 10%, pharmaceutics 9%, services sector 9%, iron & steel 8%, electro-technics and telecommunication products 7%, food processing 3% and basic materials sector (agriculture and mining) 2%.

German production in Latin America four times as high as exports to the region: The significance of the German engagement in Latin America becomes apparent from the fact that the production volume of German subsidiaries in Latin America, a total of 65.3 billion in 2001, exceeded the total German exports to the region (16 billion) by more than four times. Of the total value of German production in Latin America, according to the German central bank, around 23.5 billion were realized in Brazil and around 27.8 billion in Mexico. (The value in US$ of the production volume in Brazil has decreased due to the devaluation of the Real.) In both countries German companies account for around 5% of GDP. They participate with around 15% in the creation of value of the Brazilian industrial sector." [257]

Plans for German FDI in Brazil, according to the newspaper Estado de São Paulo, amount to a reinvestment of 7.7 billion US-dollars from German transnational corporations that already operate in Brazil. In addition to this investment, an investment in infrastructure of 10 billion US-dollars is planned. Adding these two numbers to the already realized FDI stock of currently 19 billion US-dollars would amount to an FDI stock of 36.7 billion US-dollars. With this, Germany would have the top ranking with regards to FDI stock in Brazil, even before the U.S. and Spain. [258]

And not to forget the new overall remedy, which is capable of pulling chronically indebted public budgets and companies suffering from weaknesses in demand out of any possible crisis: PPP! Public-Private-Partnership (Parceria Público-Privada in Portuguese), for example, works in the form of the dubious sell-and-lease-back principle, which is increasingly enjoying cross-boarder popularity.

Cross-border leasing is a promising model for the indebted public sector and the private sector, e.g., for the construction of roads or public institutions etc. In this sense the new pluri-annual plan (Plano Pluriannual, PPA) presented by the Lula-government in 2003 envisions several major projects to be publicly tendered on an international level. Among these projects there are several ecologically and socially doubtable projects, [259] like the waterway Rio Madeira and the large barrage Belo Monte. [260] The enlargement of the Araguaia-Tocantins-complex, however, has been provisionally stopped. The German NGO Urgewald e.V. had presented various studies in 2003 on the impact of the barrage Belo Monte, the waterway Teles-Pires Tapajós, the nuclear power station Angra III and the coal-fired power station Seival, and had concluded the these projects in part will have disastrous consequences. [261]

Angra III is the third nuclear power station in Angra, which is located on the Atlantic coast between two densely populated areas, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, in a highly sensitive area. This nuclear project had already been planned by the military dictatorship in the seventies, and was implemented at immense costs – whose consequences continue to affect the Brazilian foreign debt even today - in conjunction with the German Siemens and after consultations with the German government. [262] The original plan of the Brazilian military to develop the nuclear bomb never materialized, but the power stations were successively built – and now the completion of Angra III is on the agenda: Luiz Pinguelli Rosa, the president of Eletrobrás, expressed the hope that the French-German Framatome would invest 1.8 billion US-dollars for the completion of Angra III [263]:

"Framatome ANP is headquartered in Paris with regional subsidiaries in the U.S. and Germany. With a total workforce of 14,000, the company is active in Eastern and Western Europe, North and South America, Asia and Africa. Its annual revenues total more than 2.5 billion €. In the company, AREVA has a 66% stake and Siemens 34%." [264]

Areva is owned (numbers from 31.12.2002) with 78.96 % by the state-owned CEA (Commissariat à l’Énergie Atomique), 5.19 % belongs directly to the French state, Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations owns a share of 3.59 %, ERAP 3.21 %, EDF 2.42% and TotalFinaElf 1.02 %. [265] Frameatome would receive a license for a period of 20 years for Angra III and would be able to not only cover costs through energy sales, but would also realize profits. [266]

According to general assessment the Lula-government has a strategical aim with its PPA focused on infrastructural measures, which could help to save production costs in other sectors, especially in the production chains of exportable goods, in order to achieve a better balance of payments in the long run. [267]

According to the Brazilian Secretary of Planning, Guido Mantega, at a meeting with potential investors in Washington on December 4, 2003, [268] the Brazilian government plans a total expenditure in infrastructure of up to 100 billion US-dollars over the next four years. Other estimates envision even higher expenditures. The Estado de São Paulo from June 25, 2003 reported estimates of coming investments for the energetic sector of only 82 billion US-dollars. [269] And the Brazilian government is very interested in obtaining the participation of foreign private enterprises in these projects: Luiz Ignácio Lula da Silva, on his visit to Madrid on July 14th called on the European investors to invest in order to "create a prospering South America." [270]

And last but not least the MERCOSUR-European Business Forum (MEBF) is surely one of the most influential actors in the area of investment in the negotiating agenda between the EU and MERCOSUR. The MEBF was founded in 1999 with the objective of accompanying the free trade negotiations between the EU and MERCOSUR, - which amounts to nothing less than lobbying for their own interests in order to have them included in the agreement:

"The MEBF is based on the idea that entrepreneurs should identify MERCOSUR/EU barriers to trade , services an investment, and elaborate joint recommendations to eliminate these restrictions." [271]

The list of participants of the MEBF-conference in Buenos Aires in 2001 sounds more like a "who is who" of international corporations: Arcelor, Siemens, Alcatel, Alstom, BASF, Telefónica, Repsol YPF, DaimlerChrysler, Degussa, Ericsson, Fiat, France Telecom, Portugal Telecom, Renault, Peugeot, Bosch, Suez, ThyssenKrupp, Volkswagen and of course the German BDI and the Brazilian Sadia (whose president, now the Brazilian Secretary of Foreign Trade, does not lose sight of his poultry business) were present.

The MEBF successfully works as a lobby and pressure group [272]:

[The MEBF] "wants to use its mechanisms to give direct input into these political negotiations and thereby help to shape the face of a future trade area." [273]

Already in 1999 the MEBF boasted of its influence on political decision makers:

"The political perception of the business-driven initiative and its inaugural Conference was impressive." [274]

The MEBF considered its own lobbying as an essential catalyst in the establishment of the free trade negotiations between the EU and MERCOSUR: MEBF

"launched a campaign to get European governments to grant the European Commission a mandate for free trade negotiations with MERCOSUR. "Finally the MEBF lobbying succeeded and the EU complied with one of MEBF's most urgent demands" [MEBF Newsletter, Issue II, July 1999]." [275]

The demands of the MEBF span across the entire width of the free trade agenda, with a special emphasis on the issue of the "protection" of foreign investment. Already in 1999 the MEBF had demanded, with respect to the sector of investment in the EU-MERCOSUR free trade agreement [276]:

• national treatment for investors/investments;

• common investment rules and procedures at all governmental levels;

• non-discriminatory access to government funds, civilian research and development programs;

• free movement of capital connected to an investment including free transfer of profits;

• elimination of tax legislation, policies, and practices which discriminate against foreign investors;

• modification of respective tax laws on the treatment of foreign earned income to encourage foreign investment and to prevent double taxation;

• national security exceptions in investment should be limited, narrowly circumscribed and applied in a transparent manner;

• foreign investment protection agreements should be sped up.

In the newest version of the "Brasília Declaration" from October 30, 2003 the same demands remain, amended by formulations, which demand the immediate start of negotiations on public procurement, which declare the model of public-private-partnership to be an overall remedy and emphatically demand a broad agreement to protect investment within the FTA. [277] The issue of investment is at the top of the MEBF agenda. Investment is one of the four "new issues", which were accorded at the WTO Ministerial Conference in Singapore in 1996, which since then have been labeled the "Singapore-issues": Trade and investment, competition policy, government procurement and trade facilitation. And these so-called "Singapore-issues" are a popular object of negotiations and pipe dreams of the EU-Commission, also in the EU-MERCOSUR negotiations.

The European Commission has always praised the MEBF: In June of 1999 the then EU-commissaries Manuel Marín and Martin Bangemann had expressed their highest regard of the MEBF. [278] And interestingly enough the DG Trade seems to have adopted the MEBF declaration from October 30th as its own – how else should the circumstance be interpreted, that the Brasília-declaration can be found on the DG –trade website in the category of "related items-news" (where normally only EU press statements or documents related to "EU-MERCOSUR" can be obtained). [279]

The importance of the Singapore-issues for the European Commission should not be underestimated. EU foreign trade commissioner Pascal Lamy sees them as the motor for development:

"We have tried to explain how much we believe the Singapore issues, such as trade facilitation, are the key, not the hindrance, to development." [280]

In view of this immense significance given to the Singapore-issues by the European Commission, the BBC in the run-up to Cancún could not resist to spread the news that henceforth the focus would be on the "Brussels-issues." [281] And especially two of these Brussels-issues are of special importance for the EU: Investment and government procurement.

In this context the Commission envisions the following with respect to the investment issue:

"We believe that it is in the interest of all countries to create a more stable and transparent climate for FDI world-wide. In our view, the WTO should focus on FDI, leaving aside short-term capital movements.

Non-discrimination, transparency and predictability of domestic laws applicable to FDI should be the guiding principles for the investment framework that we envisage to negotiate.

The admission of investors should be dealt with following a gradual approach: each government should be able to decide which sectors can be opened to foreign investors and which ones cannot, according to transparent, positive and non-discriminatory commitments.

Each government should also preserve the right to regulate the economic activity within its territory, including in the fields of development, environment and social conditions.

The dispute settlement mechanism should be that of the WTO. Investor-to-State arbitration does not fit in the WTO framework, and should be left to bilateral agreements.

Rules on investment protection, for instance in case of expropriation, could also be discussed, if WTO Members found it useful. Any such rules, however, must not affect a host country’s right to regulate, in a non-discriminatory manner, the behavior of firms in its territory." [282]

At the same time, the negotiating side for the EU, after the "failure" of Cancún, seems to have made a shift in orientation:

"As far as the EU is concerned, it is suggested that we now be ready to explore alternative approaches to negotiating the Singapore issues of investment, competition, trade facilitation and transparency in government procurement, possibly through removing them from the single undertaking of the negotiations and through negotiating them as plurilateral agreements if necessary. While maintaining our substantive objects, it also suggests a slight adjustment of the approach on trade and environment and geographical indications aimed at reducing reticence to negotiations in these areas." [283]

The EU ambassador to the WTO in Geneva, Carlos Trojan, has praised the EU –proposal, to take the "Singapore issues" out of the single undertaking, as a "major shift" of EU-policy. [284] Nevertheless, it seems apparent, that Brussels does not want to take the Singapore-issues completely out of the negotiation agenda, but that it is looking for "alternative approaches" within the negotiating process. If they are taken out of the single undertaking now, the EU-Commission can still put them on the agenda later or on a bilateral level. –And the investment issue is extremely urgent for the EU, which is completely in the interest of the rights and profit margins of European corporations.

4.2 The example of Brazil: Foreign direct investment without BITs and FTAs

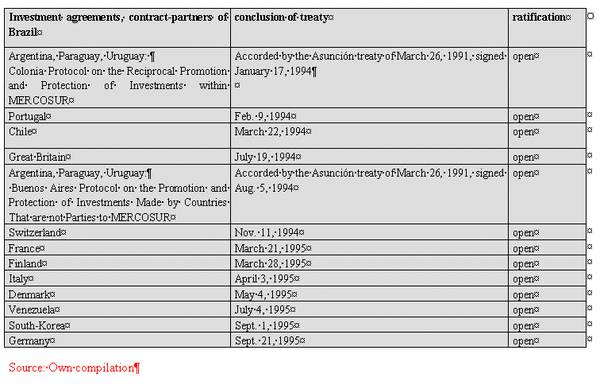

For years Brazil has been one of the leading FDI recipient nations among the "emerging countries", without having ratified one single bilateral investment treaty. [285] Brazil, after becoming a member of the MIGA (the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency of the World Bank) in 1990, has signed several bilateral investment treaties [286], however, so far none of them has been ratified by the Congresso Nacional:

The MERCOSUR agreement, "Colonia Protocol on the Reciprocal Promotion and Protection of Investments within MERCOSUR", should regulate the mutual investment conditions for foreign investors from MERCOSUR countries within the four MERCOSUR states. As a regional FTA the therein contained regulations do not have any effect on non-MERCOSUR states. The MFN clause does not extend its validity to third parties, as with bilateral investment treaties.

The "Buenos Aires Protocol on the Promotion and Protection of Investments Made by Countries That are not Parties to MERCOSUR" from August 5, 1995, however, has a special position within these treaties: Being a regional agreement on investment, it treats the role of third parties and can therefore, after its ratification, have legal consequences for other Brazilian agreements or those of other MERCOSUR states- by, e.g., causing a chain reaction in the tightly integrated net of existing investment agreements. Therefore, a study commissioned by the Brazilian National Congress recommended, that if bilateral investment treaties were to be ratified, then this agreement should be ratified first, so that its provisions can have legal effects on all following agreements. [287]

All of these agreements follow the scheme of modern bilateral investment agreements and contain dispute settlement mechanisms, also for investor-to-state disputes and the party taking legal action can freely choose the court of jurisdiction. One exception to this is the MERCOSUR-protocol, which also concedes the investor the right to choose, but the other parties (the affected state) can reject this. All agreements explicitly take the principles of MFN and NT as an orientation, and regulate the unrestricted capital and profit transfer, which cannot be obstructed by any national regulations: In the case of severe difficulties with its balance of payments the Brazilian government would be prohibited from taking any action to steer or influence the crisis, due to the international treaty.

The agreement with Switzerland, which is signed, but not yet ratified, goes further than other agreements: It is the only agreement which explicitly states that compensation payments have to be made in freely convertible currency. According to a study commissioned by the Brazilian Congress this could be in contradiction to the Brazilian Constitution. This would be the case if article 184 of the Constitution [288] was to be applied, which provides for the expropriation of unused land in the framework of the agrarian reform with compensation payments in the form of so-called "títulos da dívida agrária", i.e., compensation in no freely convertible currency. Unused land, which e.g. belongs to foreign investors, could thereby not be treated in accordance with the Constitution and the BIT at the same time: otherwise the national or the international legislation would have to be broken. [289] If this BIT, e.g., should be ratified by Brazil, then all other BITs ratified by Brazil would include these same far-reaching regulations which could be claimed by any investor coming from a country which has an investment treaty with Brazil: a chain reaction.

But even without the ratification of BITs it is not quite understandable, why foreign investors and governments demand that Brazil sign an internationally binding treaty. Brazil already has highly deregulated investment rules for FDI: The law on foreign investment of 1962 (Lei do Capital Estrangeiro LEI Nº 4.131, DE 3 DE SETEMBRO DE 1962) is still in force, which in article 2 states that all foreign capital invested in Brazil will receive identical treatment before the law as national capital, prohibiting any discriminatory measure, which is not explicitly mentioned in the law. [290]

The changes to this law, which were made in 1964 by means of the "Alteração à Lei do Capital Estrangeiro LEI Nº 4.390, DE 29 DE AGÔSTO DE 1964", only affect the modalities for the registration of foreign capital in Brazil and the modalities of capital and profit-transfers, but do not affect the essence of the principle of National Treatment defined in 1962. [291]

The establishment of a company in Brazil is linked to a juridical persona: according to the principle sole proprietor a juridical person is sufficient to establish a company, which, however, cannot be operative in the services sector. For this, two juridical persons are required to found a sociedade civil or a sociedade commercial.

Cross-border accounting between a foreign mother firm and a national subsidiary have been supervised by law since 1997, by laws IN N°243 (November 2002) and IN N°321 (April 2003), in order to prevent cross-border transfers of profits, e.g., through offshore tax havens. [292]

By international comparison the legislation for an easy transfer of capital and profits to and from Brazil is relatively soft. There are no requirements for the transfer of capital and profits, as long as the money is registered at SISBACEN (Sistema de Informações Banco Central) and can thereby be supervised by the Brazilian Central Bank. Capital transfers up to the same amount as the originally invested capital are not subjected to any tax and can be transferred abroad through SISBACEN at any time, without special permission. Amounts, which exceed the originally invested amount, can also be transferred abroad without permission and are not subjected to a transfer tax, but are subjected to the withholding tax of 15%, which would apply anyway. The declaration of these capital or profit transfers is made automatically via SISBACEN online.